United Rentals: The Roll-Up That Built America's Construction Giant

I. Introduction & Opening

Picture a construction site anywhere in North America. Before the first shovel hits dirt, before the steel goes up, before the concrete trucks arrive, someone has to deliver the equipment that makes the whole project possible. The boom lifts that send workers sixty feet into the air. The excavators that carve foundations out of rock. The generators that keep the job lit when the grid still hasn’t shown up.

Most of the time, that equipment doesn’t belong to the contractor using it. It belongs to a rental company. And more often than not, that rental company is United Rentals.

By 2022, United Rentals controlled roughly sixteen percent of the North American equipment rental market. It ran a fleet worth about $19.3 billion in original equipment cost, spread across nearly 4,700 equipment classes. And it operated a vast network of locations across the continent.

That scale shows up everywhere. If you’ve been near a major project, you’ve probably seen the blue-and-white logo on the side of a lift, a forklift, or a line of portable power units waiting their turn on a jobsite.

Wall Street has noticed too. United Rentals went public in 1997 at a split-adjusted price of about $3.50 per share. Over the years, it has traded around $800. A share held from the beginning would have turned into more than a 200x return.

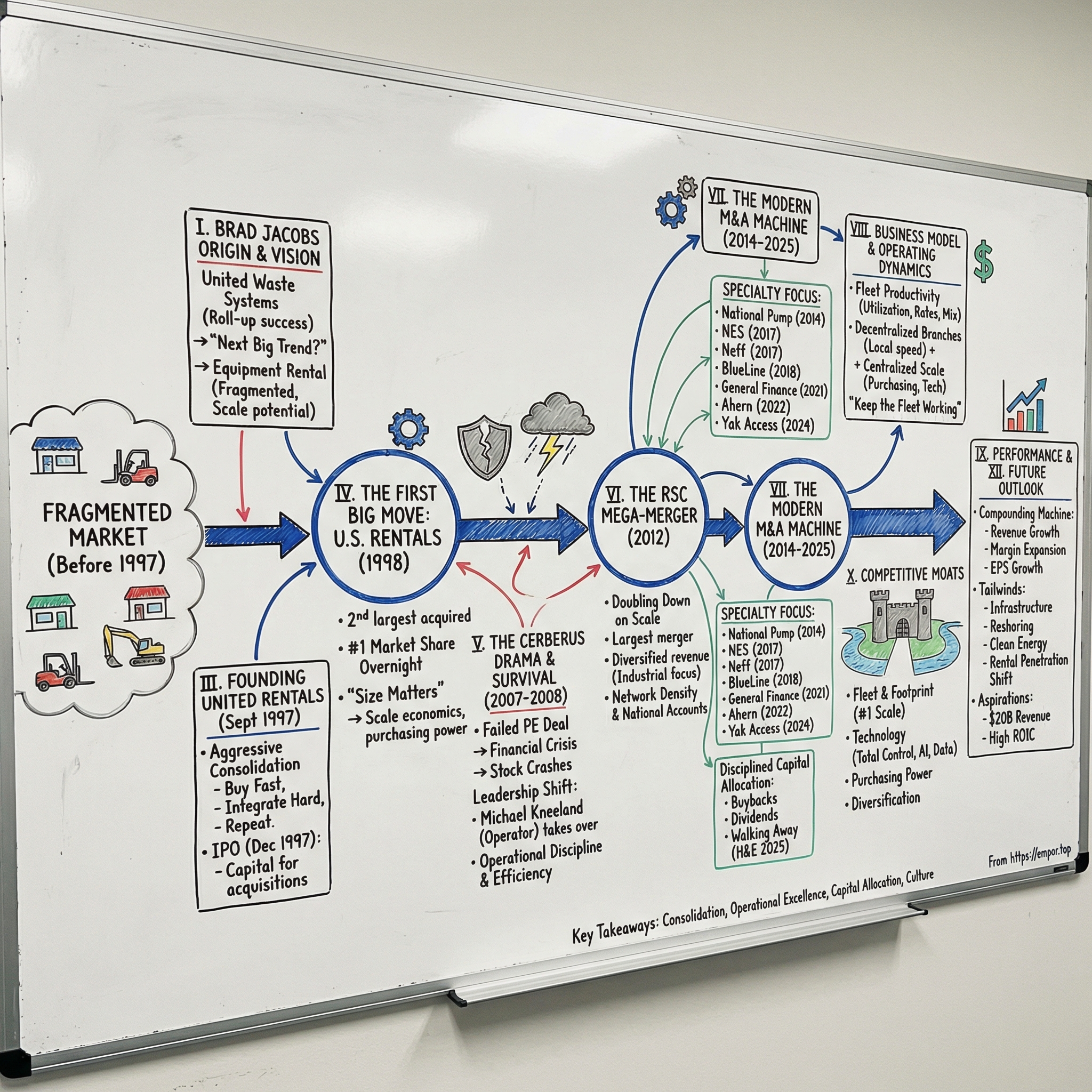

So here’s the deceptively simple question at the heart of this story: how did a serial entrepreneur take a fragmented collection of mom-and-pop rental shops and build a market leader worth tens of billions of dollars?

The answer runs through one of the most aggressive consolidation campaigns in modern American business, a private equity deal that blew up in public, a financial crisis that stress-tested the company’s balance sheet, and then, year after year, a compounding machine built on unglamorous operational discipline.

This story is really about three interlocking ideas. First: the consolidation playbook, the art and science of rolling up a messy industry. Second: operational excellence, the grind of getting more revenue days out of every piece of steel and rubber. Third: capital allocation, the discipline of deploying billions in a way that keeps compounding shareholder value.

Those three reinforce each other. Together, they explain how United Rentals became one of the most quietly extraordinary business stories of the last few decades.

One last bit of context before we rewind. The North American equipment rental industry generates more than $80 billion a year. The top three players control only about thirty percent of it. The other seventy percent is still spread across thousands of smaller operators. That gap—between the giants and everyone else—is where United Rentals was born. And it’s why this story still isn’t finished.

II. The Brad Jacobs Origin Story

On a muggy summer afternoon in Providence, Rhode Island, in the late 1970s, a college dropout named Brad Jacobs sat hunched over the financial pages, hunting for an angle.

Jacobs was born on August 3, 1956, to Albert Jordan Jacobs, a fashion jewelry importer, and Charlotte Sybil Jacobs. He grew up in the jewelry capital of America with an unusual mix of interests: classical piano on one side, mathematics on the other. He attended Northfield Mount Hermon, a boarding school in Gill, Massachusetts, and left during his junior year. He’d been recruited to Bennington College, but even that wasn’t his destination. He later transferred to Brown University, continuing with piano and math, until the pull of business overpowered the pull of school. In 1976, at twenty, he dropped out.

There’s a small detail from those years that ends up explaining a lot. Jacobs has said he’s meditated for fifteen minutes every morning and evening since he was sixteen, a practice he connects to cognitive behavioral therapy. He credits it with what he calls “radical acceptance,” the ability to take a hit, absorb it, and keep moving. It’s a nice life habit in your twenties. It’s a survival trait when your career becomes a string of billion-dollar bets.

The first bet came fast. In 1979, at twenty-three, Jacobs co-founded Amerex Oil Associates, an oil brokerage firm. He’d read about brokers during the late-1970s energy spikes and simply cold-called his way into the business. Along the way, he pulled off a coup for a kid with no degree: he brought in Ludwig Jesselson, the head of commodity house Phillip Brothers, as a mentor.

Amerex scaled quickly. Jacobs grew it to about $4.7 billion in annual gross contract volume with offices on three continents, and he served as CEO until selling the business in 1983. He was twenty-seven. Most people that age are still trying to get promoted. Jacobs had already built something global and exited.

He wasn’t done. In 1984 he moved to London and founded Hamilton Resources, an oil trading company. For five years he lived the life: securing crude from places like Russia and Nigeria, chartering ships, and moving product into European refineries. Jesselson left him with a simple rule that Jacobs would carry into every industry he touched: you can mess up a lot in business and still do well as long as you get the big trend right.

By the late 1980s, Hamilton Resources was generating roughly a billion dollars in revenue. But the game was changing. Futures markets were compressing the profits of old-school, globe-trotting arbitrage. Jacobs saw the squeeze coming and did what he’d been trained to do: step back, stop fighting the tide, and go find the next big trend.

He found it in garbage.

In 1989, Jacobs founded United Waste Systems in Greenwich, Connecticut. His thesis was almost offensively simple. Across rural America, thousands of small, family-owned haulers ran overlapping routes. Their trucks passed each other on the same roads, day after day, collecting the same kind of waste from neighboring customers—duplicating fuel, drivers, maintenance, and overhead just to do the same work.

The inefficiency wasn’t subtle. If you could buy two operators in the same area and combine their routes, you didn’t need two trucks and two drivers anymore. You could run one, cut the redundant costs, and keep the revenue. It was consolidation as applied math.

The spark came from reading an analyst report about the fat margins at Browning-Ferris Industries, one of the major players. Jacobs dug in—interviewed managers, learned from two former Browning-Ferris executives that the big companies had systematically ignored rural areas, and realized that was where a roll-up could work best. He hired those executives and started buying.

He moved with ferocious focus: acquire three or four small haulers in the same geography, integrate them, and rationalize operations. Route density improved. Trucks ran fuller. Back-office costs got spread over a larger base.

And just as important, the sellers were there. Many of these businesses were run by aging owners with no succession plan, trying to keep old fleets on the road while regulations kept piling up. Jacobs offered something they wanted: cash, certainty, and a clean exit.

By 1992, United Waste had grown big enough to go public on NASDAQ. Then it turned into what Jacobs loves most: a compounding machine.

Over the next five years, he completed roughly two hundred acquisitions. United Waste expanded into twenty-five states, with eighty-six collection companies, forty landfills, and seventy-nine transfer and recycling stations. From the IPO to the sale, the stock outperformed the S&P 500 by 5.6 times and delivered a fifty-five percent compound annual return—year after year—in the business of picking up trash.

In August 1997, Jacobs sold United Waste Systems to USA Waste Services in a deal valued at $2.5 billion. He personally netted roughly $120 million from an original $3 million investment. He was forty-one.

He’d built the fifth-largest solid waste company in North America from nothing. He could’ve stopped there—bought more time, played more piano, enjoyed the win. Instead, he did the most Brad Jacobs thing possible: he went hunting for the next industry.

The search wasn’t casual. Jacobs and the senior team that had helped him execute the United Waste playbook—many of whom came with him—worked through fragmented markets one by one. They had a checklist: big market, lots of small operators, little product differentiation, real synergies from scale, and ideally a seller base of owners ready to retire.

Equipment rental checked every box.

As Wall Street Journal reporter Steven Lipin later put it, Jacobs arrived at a blunt conclusion: “This industry is ready to be consolidated.” The market was enormous, but power was scattered across thousands of independent rental yards—many family-run, many with no clear successor.

So Jacobs did what he always did: he bet on the thesis with his own money. According to Forbes writer Silvia Sansoni, he and his senior management team pooled $46.5 million of personal wealth, raised another $8 million, and started talking to underwriters. That’s not “management alignment” as a slide in a pitch deck. That’s a team choosing to put real skin in the game after they’d already made enough to walk away.

Then came the hard part: finding targets.

In waste, you could map routes and identify operators. In equipment rental, the landscape was private and opaque—little public record, few obvious databases. Jacobs responded with sheer grind. He read five years of trade magazines. He downloaded hundreds of rental store websites. He hired a private investigation firm with access to dozens of databases. And he combed through listings to identify mom-and-pop shops worth buying.

He didn’t wait for deals to come to him. He went out and built the list himself.

III. Founding United Rentals: The Blueprint (1997)

In September 1997—weeks after selling United Waste Systems—Jacobs incorporated United Rentals. The pace was the point. Plenty of founders would have taken time to breathe after a multibillion-dollar exit. Jacobs didn’t. He stepped in as chairman and chief executive officer and immediately started running the same playbook he’d just proven in waste: find a fragmented industry, buy fast, integrate hard, repeat.

He also brought the same bench.

United Rentals launched with a leadership team pulled almost entirely from the United Waste brain trust: eight officers in total, including Wayland R. Hicks as vice chairman, president, and chief operating officer; John N. Milne as vice chairman and chief acquisitions officer (the same role he’d held at United Waste); and Michael J. Nolan as chief financial officer.

This wasn’t a group learning roll-ups for the first time. They’d already stitched together hundreds of small businesses. Jacobs had a simple way of framing it: the management team was the product, the companies they acquired were the raw material, and the consolidated company was the finished good.

The early strategy was clear: move faster than everyone else and get big before the rest of the industry could fully respond. Equipment rental was fragmented, but it wasn’t sleepy. Other consolidators—like RSC Equipment Rental and Hertz Equipment—were also buying. They just weren’t moving at Jacobs speed.

Jacobs’ edge was urgency and audacity. He wanted the best businesses on his terms, not in a bidding war later.

So he started buying immediately. In October 1997, United Rentals acquired six small leasing companies—its first set of building blocks—chosen less for overlap than for coverage. The goal was a geographically diversified footprint across the United States and Canada from day one, not a cluster in a single metro area.

And those deals brought more than iron. They brought branch managers who knew their markets, relationships with contractors who needed equipment tomorrow morning, and local operating know-how that’s hard to replicate from headquarters.

Then came the move that turned a roll-up into a rocket ship: the public markets.

In December 1997, just three months after forming, United Rentals began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker URI. The IPO priced at $13.50 per share and raised about $100 million. A second offering in March 1998 brought in another $200 million. In other words, in roughly half a year, the company pulled in about $285 million of equity—fresh fuel for the acquisition engine.

The speed was almost unheard of, but Jacobs understood what mattered: access to capital, and a tradable currency.

Being public gave him three advantages at once. First, stock—something many sellers would accept as part of the price. Second, a repeatable way to raise more money as the deal pipeline grew. And third, a visible valuation that made the pitch to a family-owned rental yard much easier. When an owner is staring at a public acquirer with a quoted price on the screen and a story the market is rewarding, selling feels less like surrender and more like upgrading.

The blueprint itself was straightforward, and brutal in execution: buy in fragmented markets where consolidation could create real synergies, close quickly, and integrate onto common systems and standards. Use the growing cash flow base to fund the next wave. Keep reinvesting in fleet and technology so the combined company became genuinely better—not just larger.

From late 1997 into early 1998, the cadence was relentless. Deals kept closing, branches kept lighting up on the map, and the network kept getting denser. It looked less like a traditional corporate development process and more like a campaign: targets identified, diligenced, negotiated, signed—over and over.

Because the objective wasn’t simply to be the biggest name in rental. It was to reach the kind of scale where the economics changed—where purchasing power, utilization, logistics, and overhead created a structural cost advantage over the independents. A moat that widened with every acquisition.

Forbes summed up the audacity of the moment with a 1998 headline: “In just eight months Brad Jacobs has built a $300 million company that rents construction equipment -- all thanks to the information age.”

IV. The First Big Move: U.S. Rentals Acquisition (1998)

United Rentals’ first truly defining swing came in June 1998—barely nine months after the company had been created. It announced that it would acquire U.S. Rentals, Inc. of Modesto, California, in an all-stock merger valued at roughly $1.2 to $1.31 billion, including assumed debt.

U.S. Rentals wasn’t some regional mom-and-pop yard. Founded in 1957, it was the second-largest equipment rental company in North America. Overnight, the deal vaulted United Rentals into the number-one spot on the continent, with about $1.5 billion in annual sales and close to three hundred locations across thirty-three states, plus Canada and Mexico.

It’s hard to overstate how aggressive this was. United Rentals wasn’t even a year old—and it was buying one of the best-known incumbents in the business for over a billion dollars. Jacobs wasn’t trying to win patiently. He was trying to win before the rest of the industry fully understood what was happening.

The exchange ratio captured the confidence: each share of U.S. Rentals stock would convert into 0.9625 shares of United Rentals. Around the deal, Jacobs delivered a line that would come to define the whole strategy: “Size definitely does matter” in equipment rental.

The problem, of course, was that size only matters if you can actually run it.

Integration was messy. Now United Rentals had to stitch together two large, geographically scattered operations—align technology systems, standardize procedures across hundreds of branches, decide what to do with overlapping locations, and manage the very human friction of combining two cultures.

Every branch had its own rhythms: how it priced, how it dispatched, how it serviced equipment, how it dealt with contractors who needed a machine at 7 a.m. sharp. Many employees had been doing the job the same way for years. Asking them to change systems, processes, and reporting lines—while still keeping customers happy—was the kind of complexity that breaks roll-ups.

And this is where many consolidators die: they buy faster than they can digest. United Rentals felt that strain. Deal-making had been so relentless that the organization was often playing catch-up, learning in real time the difference between acquiring a business and actually making it part of one.

Still, the underlying thesis didn’t crack. As the combined company started to settle, the advantages of scale showed up in places that mattered.

Purchasing leverage became real. A bigger fleet meant more clout with manufacturers like Caterpillar and JLG. When you become the biggest buyer, you don’t just get better economics—you get a different relationship. Technology investments started to pay off too, because systems that were expensive for a regional chain made sense when spread across a national footprint. And national accounts—the big customers running projects across multiple states—began to see United Rentals as the only operator that could deliver consistent service wherever they were building.

This era became the forge for the United Rentals playbook. Over the decade Jacobs led the company, it completed roughly 250 acquisitions—an astonishing pace, sustained for years. United Rentals grew from those first six small purchases into a Fortune-ranked public company, and it became one of the best-performing stocks in the Fortune 500 over that period.

The model kept sharpening: diligence that emphasized fleet quality and customer relationships, not just the numbers; rapid conversion onto standard systems; aggressive removal of overlapping costs; and a structure that left real autonomy at the branch level while centralizing the functions where scale created an advantage—purchasing, finance, and planning.

Because in fragmented industries, the magic isn’t simply buying businesses. The value comes from making the combined company operate better than the pieces ever could on their own.

United Rentals wasn’t just getting bigger. It was building capabilities—technology, procurement power, national sales coverage, fleet analytics—that smaller competitors couldn’t reasonably match. Each layer reinforced the others. The moat deepened. And soon, it would be tested in a way no integration plan can fully prepare for.

V. The Cerberus Drama & Leadership Transition (2007-2008)

By early 2007, private equity was at full boil. Leverage was cheap, megadeals were everywhere, and United Rentals—now a proven cash-generating machine—looked like the kind of asset buyout firms loved. Inside the company, there was a growing sense that public markets weren’t giving United Rentals full credit for what it had become.

So the board did what boards do when they think Wall Street has it wrong. On April 10, 2007, United Rentals announced it was exploring “strategic alternatives”—a tidy, corporate phrase that essentially meant: we’re open for business.

The timing, on paper, was impeccable. Private equity firms were flush with capital. Banks were eager to lend. The LBO machine was humming.

On July 23, 2007, United Rentals announced a definitive agreement to sell itself to Cerberus Capital Management in a transaction valued at about $6.6 billion, including roughly $2.6 billion of assumed debt. Shareholders would get $34.50 per share in cash, a meaningful premium to where the stock had been trading. A group of banks—Bank of America, Credit Suisse, Morgan Stanley, and Lehman Brothers—lined up to finance the deal. Apollo Management affiliates, with about eighteen percent of the vote, agreed to support it.

And then the floor dropped out from under the entire credit market.

The summer of 2007 was the start of the unwind. Bear Stearns’ subprime hedge funds imploded in June. By August, lending between banks was freezing up. The debt that had made buyouts so easy to pencil suddenly wasn’t easy at all. Banks that had promised financing were staring at commitments they couldn’t syndicate. Across the deal world, transactions that had looked “done” started to wobble.

United Rentals’ deal didn’t wobble. It snapped.

On November 14, 2007, the company announced that Cerberus was not prepared to proceed on the agreed terms. The key detail was what Cerberus did not claim: it confirmed there had been no material adverse change at United Rentals itself—the contractual escape hatch that would have allowed it to walk away cleanly. The business, by their own admission, wasn’t the problem.

The problem was the environment. Cerberus didn’t want to close a highly leveraged buyout in a world where the financing was suddenly far more expensive, or potentially unavailable. United Rentals’ stock was crushed, dropping more than thirty percent on the news.

The company sued, arguing that Cerberus was trying to use market chaos as leverage—“nothing more than a naked ploy to extract a lower price.” The fight went to the Delaware Chancery Court, the arena where America’s biggest corporate contract disputes get decided. A two-day trial followed in mid-December. The issue sounded technical but carried enormous stakes: could Cerberus be forced to close under the merger agreement’s specific performance language, or was the $100 million termination fee the “sole and exclusive” remedy if it refused?

On December 21, 2007, the Vice Chancellor ruled against United Rentals. He called it “a good, old fashioned contract case prompted by buyer’s remorse,” and while he noted that “one may plausibly upbraid Cerberus for walking away,” he concluded the agreement didn’t give United Rentals the right to force the closing. The court found the contract ambiguous and sided with Cerberus’ interpretation—especially given evidence that Cerberus had insisted in negotiations that the termination fee would cap its liability.

Cerberus paid the $100 million fee and walked. On a $6.6 billion deal, it was barely more than a cost of doing business. Andrew Ross Sorkin captured the mood at the time, writing that “Cerberus just proved itself to be the ultimate flighty, hot-tempered partner.”

The case became a warning shot across the M&A world. It was one of the landmark deal disputes of that era, and it pushed lawyers and boards toward tighter merger agreements—stronger specific performance provisions, clearer remedies, and more carefully structured reverse breakup fees.

For United Rentals, there was no time to admire the legal precedent. The company had been left standing alone at the exact moment the construction economy was about to take a historic hit.

The financial crisis rolled in, and the industry turned down hard. Construction spending cratered. United Rentals’ revenue fell sharply. The stock, once priced for a buyout, eventually sank below five dollars per share.

Management had to go into survival mode: cutting costs, closing branches, reducing headcount, and pulling back on capital spending. This was the stress test—of the business model, the balance sheet, and the organizational muscle the roll-up years had built.

Brad Jacobs, meanwhile, was already moving on. He had stepped down as CEO at the end of 2003 but remained executive chairman. In August 2007, shortly after the Cerberus deal was announced, he resigned from the board to pursue new opportunities.

He would later run the same consolidation playbook in another corner of the economy, founding XPO Logistics in 2011 and rapidly building it into a major transportation and logistics company. He later spun off GXO Logistics and RXO from XPO. Most recently, in 2024, he launched QXO, Inc., setting his sights on the building products distribution sector. The pattern remained consistent: find a big, growing, fragmented industry where technology is underused, buy businesses at reasonable prices, and improve them through operational execution. Over time, that approach produced eight separate billion-dollar companies.

Back at United Rentals, the moment demanded a different kind of leader than a deal-hunting founder. It demanded an operator.

That operator was Michael Kneeland. Kneeland had joined United Rentals in 1998 through the acquisition of Equipment Supply Company, where he’d been a general manager. Before that, he was president of Free State Industries, giving him decades of hands-on experience in the equipment rental business. During the Cerberus turbulence, he served as interim CEO beginning in mid-2007. In August 2008, the board unanimously elected him as president, CEO, and director on a permanent basis.

Kneeland wasn’t a headline-grabbing, acquisitive CEO in the Jacobs mold. He was the steady hand: someone who’d run branches, managed regions, and understood the day-to-day mechanics of the business—how equipment gets maintained, moved, priced, and kept earning. Under his leadership, United Rentals tightened its focus on fleet utilization, service performance, and operational efficiency. He also introduced what became a defining internal filter for M&A: “Are we a better owner?” It forced the company to justify acquisitions with real operational improvement potential—not just deal math.

And here’s the twist that only becomes obvious in hindsight.

In 2007, the failed Cerberus deal looked like a disaster. Shareholders had been offered $34.50 per share. The stock collapsed. The economy was falling apart.

But surviving the downturn as an independent public company—rather than being taken private and loaded with buyout leverage—ultimately created vastly more value than the deal ever could have. The same shareholders who would have been cashed out in 2007 were, years later, watching the stock trade north of $800.

What felt like catastrophe in the moment became, over the long arc of the story, one of the luckiest breaks United Rentals ever got.

VI. The RSC Mega-Merger: Doubling Down (2012)

By late 2011, the construction industry was finally crawling out of its worst downturn in decades. United Rentals had survived, stabilized, and regained its footing. Now it was ready to do something big—big enough to reshape the industry the way the U.S. Rentals deal had back in 1998.

On December 16, 2011, United Rentals announced a definitive agreement to acquire RSC Holdings, the second-largest equipment rental company in North America, based in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The price was about $4.2 billion in a cash-and-stock deal. RSC shareholders would receive $18 per share—a hefty premium to where the stock had been trading—paid as $10.80 in cash plus 0.2783 shares of United Rentals stock. It was, at the time, the largest merger in equipment rental history.

RSC wasn’t a bolt-on. It ran 452 branch locations across forty-two U.S. states and three Canadian provinces, with a fleet of roughly $2.7 billion in original equipment cost and about 4,600 employees. It had its own systems, its own culture, and long-standing customer relationships—especially in industrial, maintenance, and non-residential construction.

Putting the industry’s number one and number two together wasn’t a merger. It was a tectonic event.

The strategic logic wasn’t just “more share.” Yes, the combined company jumped to roughly a thirteen percent market share. But more importantly, the revenue mix changed in a way that made United Rentals structurally more resilient. Industrial exposure increased sharply, while reliance on commercial construction fell. In a cyclical business, that kind of diversification isn’t a nice-to-have—it’s shock absorption.

Financing came through roughly $2.825 billion of new notes. Oak Hill Capital Partners, which owned 33.5 percent of RSC, agreed to vote its shares in favor. The corporate cleanup was handled too: RSC’s domestic subsidiaries were merged into a newly formed operating company that was renamed United Rentals (North America), Inc. Three independent RSC directors joined United Rentals’ board.

The deal closed on April 30, 2012. Then came the hard part.

Integration at this scale isn’t a checklist—it’s hundreds of decisions made under real-world pressure. In every market where both companies had branches, United Rentals had to decide which locations stayed open, which closed, and how to move equipment, customers, and staff without service falling apart. Technology platforms had to be consolidated. Pricing had to be aligned. Two sales organizations had to stop competing and start operating as one.

The company projected more than $200 million in annual cost savings, with about two-thirds expected in the first year. And this is where you could see the difference between United Rentals in the late 1990s and United Rentals in 2012. The early roll-up era had taught the organization how to digest acquisitions without breaking. Dedicated integration teams went region by region. Timelines were clear. Milestones were tracked. The synergies were real—and they came through faster than many expected.

But the real payoff wasn’t just cost. It was capability.

After RSC, United Rentals had a network dense enough, and a fleet broad enough, to become the default answer for national accounts—the customers that run multi-site projects across multiple states and want one contract, one set of standards, and one provider that can deliver the same experience everywhere.

If you’re building in Texas, California, and New York, stitching together three local rental relationships is friction. United Rentals could remove that friction: one partner, consistent equipment quality, integrated systems, and the scale to deliver.

The merger also rewired the industry’s competitive landscape. Before the deal, there were two giants of roughly similar weight and thousands of smaller operators underneath them. After it, there was one dominant player, a smaller set of midsized competitors, and a still-fragmented long tail. The gap widened—and every major acquisition made it harder for rivals to find enough scale to catch up.

For investors, RSC marked the start of a remarkable run. In June 2014, United Rentals first appeared on the Fortune 500 at number 500. That same year, in September, it was added to the S&P 500 Index. From there, the company kept climbing. Diluted earnings per share grew from $0.79 in 2012 to more than $38 by 2025—growth driven by the underlying business and amplified by a share count that kept shrinking through buybacks.

And it all tied back to the operator Jacobs had handed the keys to in the crisis.

Under Michael Kneeland’s leadership from 2008 to 2019, United Rentals expanded from roughly 530 locations to more than 1,200, from about 7,500 employees to nearly 19,000, and from roughly $2.6 billion in revenue to nearly $9.4 billion. He oversaw around $8 billion of acquisitions and built the specialty segment from a modest add-on into a core pillar of strategy, expanding to more than 340 specialty locations by the time he retired.

When Kneeland stepped down as CEO in May 2019, he passed the baton to Matthew Flannery. Kneeland stayed on as non-executive chairman of the board—a role he continues to hold.

VII. The Modern M&A Machine (2014-2025)

If the RSC merger was the moment United Rentals became the clear heavyweight, the decade that followed was how it stayed there. This wasn’t splashy, founder-led dealmaking. It was a repeatable, disciplined M&A machine—one that used acquisitions to widen the moat, not just pad the map.

Matthew Flannery, who took over as CEO in May 2019 after serving as COO since 2012 and president since 2018, was built for that kind of compounding. He’d joined United Rentals back in 1998 through the acquisition of Connecticut-based McClinch Equipment and worked his way up the hard way—branch manager, district sales manager, regional vice president, head of eastern operations—before moving into the C-suite. He was an operator first, with deep on-the-ground instincts, and he inherited the financial discipline Michael Kneeland had embedded. Under both leaders, the rule was consistent: every deal had to do at least one of three things—fill a geographic gap, add a specialty capability, or take out a competitor. The best ones did two or three at once.

The first major move in this era came in March 2014, when United Rentals announced it would acquire National Pump for $780 million. The deal closed that same month and made United Rentals the second-largest pump rental company in North America. On the surface, pumps might sound like a niche. In reality, they’re a high-value specialty category—used for construction dewatering, industrial jobs, and environmental remediation—and they fit perfectly with where United Rentals wanted to go: toward specialty rentals with more expertise, more stickiness, and better margins.

The logic was simple and powerful. If you’re already delivering a boom lift to a jobsite, why not also deliver the pump that keeps the excavation dry, the generator that powers the site, and the trench shoring that keeps crews safe?

That specialty push continued with the acquisition of NES Rentals for $965 million in cash. NES was an aerial-focused rental company, serving about 18,000 customers across industrial and non-residential construction. It was based in Chicago, had 73 branches, and about 1,100 employees, with a footprint concentrated in the eastern half of the U.S. The deal closed on April 3, 2017, strengthening United Rentals’ position in one of the category’s most important and fast-moving fleets: aerial work platforms.

Later that year, United Rentals acquired Neff Corporation, adding roughly $867 million in equipment and 69 rental locations.

In 2018, the pace stayed brisk with two notable deals. First, United Rentals acquired BakerCorp International Holdings for $715 million, expanding its fluid solutions business and picking up a European footprint in countries including France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands.

Then came BlueLine Rental. In September 2018, United Rentals agreed to buy BlueLine from Platinum Equity for about $2.1 billion in cash. BlueLine operated 114 locations across 25 U.S. states, Canada, and Puerto Rico, with around 46,000 rental assets.

BlueLine mattered not only because it was big, but because it brought a different kind of customer. BlueLine skewed toward smaller, local accounts—exactly the segment United Rentals’ national-account strength could sometimes miss. In effect, United Rentals bought relationships and reach that would have taken years to build organically.

In May 2021, United Rentals bought General Finance Corporation, expanding further into specialty with portable storage containers, mobile offices, and modular space through brands like Pac Van, Container King, and Royal Wolf in Australia and New Zealand. Strategically, it fit the theme—adjacent rentals with strong demand and practical use cases. Geographically, it did something else: it gave United Rentals its first meaningful presence in Asia-Pacific, a real step beyond its North American core.

The biggest deal of the early 2020s came in December 2022, when United Rentals completed the acquisition of Ahern Rentals for about $2.0 billion in cash. Ahern, the eighth-largest rental company in North America, brought 106 facilities across 30 states, roughly 2,100 employees, and about 60,000 rental assets. It also added meaningful density in the western U.S., strengthening United Rentals where growth and fleet availability really mattered.

Then, in March 2024, United Rentals closed one of its most interesting specialty adjacencies: the acquisition of Yak Access and affiliates for approximately $1.1 billion from Platinum Equity. Yak was a business most people never think about—until they need it. It provided access solutions for construction sites, pipeline routes, and utility corridors in soft or environmentally sensitive terrain, using surface protection mats. Its footprint included about 600,000 hardwood, softwood, and composite mats across more than 40 states and 135 distribution points.

Financially, Yak brought $353 million in revenue and $171 million in adjusted EBITDA. United Rentals bought it for about 6.4 times EBITDA, falling to about 5.2 times after tax benefits and synergies. Strategically, the deal created a new specialty line: Matting Solutions. And it moved quickly. By 2025, the Yak matting business had grown 55 percent as reported and was ahead of management’s target to double the business within five years of the acquisition.

All of this ties to the most important shift in United Rentals’ modern history: specialty stopped being an add-on and became a core engine. By 2025, specialty rental revenue had reached $4.6 billion, up nearly fourteen percent year over year, and accounted for about a third of total rental revenue—up from roughly fifteen percent a decade earlier.

That mix shift mattered because specialty tends to be better business. It generally carries higher margins—gross margins near forty-four percent versus about thirty-five percent for general rentals. It deepens customer relationships because the offering often includes technical expertise and consultation, not just equipment on a trailer. It sees less direct price competition, because fewer players can show up with both the gear and the know-how. And it can be less cyclical, since categories like trench safety or emergency power are often driven by regulation, maintenance needs, and weather events, not just new construction starts.

Not every swing, however, ended in a closing dinner.

In January 2025, United Rentals announced an agreement to acquire H&E Equipment Services for $92 per share, valuing the deal at roughly $4.8 billion in total enterprise value. H&E had about 160 branches across 30 states, nearly $3 billion in fleet, and roughly 2,900 employees—an acquisition with clear strategic logic.

But during the 35-day go-shop period, Herc Holdings came in with a higher bid: $104.59 per share in cash and stock, valuing H&E at about $5.3 billion. United Rentals chose not to chase. It walked away on February 18, 2025, collected a $63.5 million termination fee, and immediately restarted its share repurchase program.

Herc completed the H&E acquisition in June 2025, ending up with 613 locations and about $5.1 billion in pro forma revenue. And for United Rentals, the episode revealed something that often matters more than any individual deal: the discipline to walk away, even when the asset fits, and even when the headlines would have been flattering.

VIII. Business Model & Operating Dynamics

To understand why United Rentals compounds the way it does, you have to zoom in from the M&A headlines to the day-to-day mechanics. From the outside, equipment rental looks straightforward: you own machines, you rent machines. In practice, it’s an operations-heavy business where small improvements in execution create outsized financial results.

At its core, United Rentals buys construction and industrial equipment, rents it out for days, weeks, or months, and then sells that equipment into the used market when it’s no longer optimal for the fleet. It’s asset management—except the assets are boom lifts, excavators, compressors, and generators instead of stocks and bonds.

By 2025, the fleet spanned nearly five thousand classes of equipment with about $22.5 billion in original equipment cost. That scale creates the real job: maintain everything, track it, move it, deliver it, pick it up, and ultimately dispose of it—across hundreds of thousands of individual units scattered around the continent.

United Rentals’ revenue comes from three main streams. The biggest is equipment rentals, at about eighty-five percent of total revenue. That’s the core product: customers paying daily, weekly, or monthly rates for equipment they don’t want—or can’t afford—to own.

Next comes sales of rental equipment, essentially the company’s used-equipment disposal machine, at roughly nine percent. The rest comes from selling new equipment, contractor supplies, and related services.

The entire model turns on one deceptively simple idea: keep the fleet working. Every machine sitting idle in a yard is still depreciating, still taking up space, still needing maintenance and management—while generating zero revenue. Every machine out on a jobsite is earning rental income that helps cover the fixed costs of branches, technicians, delivery trucks, and the people coordinating it all.

That’s why fleet utilization is so powerful. In this business, a few points of improvement can swing profitability meaningfully, because once the branch network is built, a lot of the incremental revenue drops through after fixed costs are covered.

United Rentals doesn’t emphasize raw utilization in public reporting. Instead it uses a proprietary composite metric called fleet productivity, which rolls together three levers: rental rates (what you charge), time utilization (how often the equipment is actually out on rent), and mix (what equipment is being rented, to which customers, and where). In 2025, fleet productivity increased 2.2 percent year over year—an indicator that the company was pushing the right buttons across pricing, utilization, and fleet mix.

Operationally, United Rentals runs through two reportable segments.

General Rentals is the bread-and-butter fleet: aerial work platforms like boom and scissor lifts, earthmoving equipment like excavators and backhoes, material handling equipment like forklifts and telehandlers, plus tools and light equipment. In 2025, General Rentals produced $9.2 billion in rental revenue.

Specialty is the higher-margin set of businesses that increasingly defines modern United Rentals: trench safety for underground work, temporary power and mobile climate control, fluid solutions including pumps, portable storage and modular space, and ground protection matting through the Yak acquisition, among others. Specialty delivered $4.6 billion in rental revenue in 2025, with gross margins near forty-four percent versus about thirty-five percent in General Rentals. That margin gap is the cleanest explanation for the strategic shift toward specialty: it’s stickier, more technical, and typically less exposed to pure price competition.

To make all of this work, branch economics matter—a lot. Each of the roughly 1,700 locations functions as a local hub: equipment storage, maintenance, dispatch, delivery, and customer relationships. Branch managers effectively run a local business inside the larger system, making daily decisions about customer needs, fleet allocation, and service levels.

The model is deliberately decentralized where speed matters and centralized where scale matters. Branches get the autonomy to react to local demand, while the parent company brings purchasing power, technology, and financial discipline. The management stack runs from branch to district (typically five to fourteen branches), to region, to division—layers designed to keep accountability tight while still letting local operators operate.

If there’s one core competency that separates winners from everyone else, it’s fleet management. United Rentals takes a lifecycle approach: constantly monitoring repair and maintenance costs, utilization patterns, and residual values to decide when each piece of equipment should stay in the rental fleet and when it should be sold. A typical unit might be held for around seven years, though the range varies widely depending on category and usage.

Disposal is managed through four channels, in order of preference. Retail sales to customers tend to generate the best recovery. Then come trade-in packages with manufacturers, followed by wholesale sales to dealers. Auctions are the least preferred channel, largely because commissions can take ten to twelve percent of the sale price. In 2025, the company recovered roughly half of original equipment cost on used equipment sales.

The customer value proposition becomes obvious with a simple example. A contractor doing a bridge job in rural Montana doesn’t want to tie up capital in a $200,000 excavator that will sit unused for most of the year after the project ends. Renting turns that excavator from a single-company burden into a shared resource. United Rentals can send the same machine from Montana to a highway project in Wyoming the next week. The customer preserves capital and avoids idle time; United Rentals keeps the asset earning. That’s the basic bargain—and it gets more powerful as the network gets larger.

This is where network density becomes a structural advantage. With more than 1,660 locations in North America, United Rentals can serve virtually any jobsite within a reasonable window, and branches don’t have to carry every type of equipment to meet customer demand. They can share fleet across the network. If a branch in Tucson needs a specialized trench box it doesn’t stock, it can pull one from Phoenix. The customer sees one company that can say “yes.” Behind the scenes, it’s a logistics and technology system that turns scale into higher utilization, better service, and better economics.

IX. Financial Performance & Capital Allocation

The numbers tell a story of relentless compounding. In 2025, United Rentals reported total revenue of $16.1 billion, up about five percent from $15.3 billion the year before. Equipment rental revenue reached $13.8 billion. Adjusted EBITDA came in at $7.3 billion, for a margin of roughly 45.5 percent.

That margin is the kind of thing people associate with software, not with a company whose product is heavy equipment moving in and out of yards on flatbed trucks. But it makes sense once you understand the operating model. When you already have the branch, the yard, the maintenance shop, the dispatch team, and the delivery fleet in place, renting one more machine doesn’t require building a whole new cost structure. A lot of the incremental revenue drops through. That’s operating leverage—at industrial scale.

Cash flow shows the same pattern. In 2025, free cash flow was $2.2 billion, even after $4.2 billion of gross rental capital expenditures. In other words: the company spent more than $4 billion buying fleet and still produced more than $2 billion of free cash. Operating cash flow reached $5.2 billion, up from $4.5 billion in the prior year. This is what it looks like when a capital-intensive business is run with discipline.

And that discipline shows up most clearly in capital allocation. United Rentals has been explicit about the priorities: keep leverage conservative, invest enough to keep the fleet young and productive, stay ready for acquisitions when they’re truly attractive—and return most of the remaining free cash flow to shareholders.

In 2025, the company returned $2.4 billion to shareholders, including $1.9 billion in share repurchases and $464 million in dividends.

For 2026, management guided to roughly $2 billion in total shareholder returns. That included a ten percent increase in the quarterly dividend to $1.97 per share, plus $1.5 billion of planned buybacks. And to keep the buyback engine stocked, the board approved a new $5 billion share repurchase authorization with no expiration date.

Buybacks have been a major driver of per-share compounding. Since 2012, United Rentals has repurchased about $5.3 billion of its own stock, cutting the share count by more than twenty-five percent. When the business grows earnings and the company reduces the number of shares those earnings are spread across, per-share results can accelerate fast.

You can see it in the earnings line: diluted EPS rose from $0.79 in 2012 to $38.69 in 2024 and $38.68 in 2025. The nearly flat year-over-year result in 2025 wasn’t a sign the core engine stalled—it reflected higher depreciation from the Yak Access fleet and a restructuring program.

Still, markets can be unforgiving in the short term. In Q4 2025, adjusted EPS of $11.09 came in below analyst consensus of roughly $11.63. After the January 28, 2026 earnings report, the stock fell around fifteen percent in the following days before partially recovering.

The same mindset shows up in M&A. Management screens deals against return thresholds and looks for transactions where synergies can meaningfully reduce the effective price—often aiming to bring the multiple down into the five-to-six-times EBITDA range. Yak Access is a clean illustration: about 6.4 times EBITDA at purchase, falling to about 5.2 times after tax benefits and synergies. And the decision to walk away from H&E—taking the termination fee rather than chasing a higher bid—was the clearest proof that this discipline isn’t just talk.

On the balance sheet, United Rentals ended 2025 with net leverage of 1.9 times, within management’s target range. Total liquidity was $3.3 billion. Return on invested capital was about 11.7 percent, down from 13 percent in 2024, with an aspirational target of fifteen percent or more by 2028.

Those 2028 aspirational targets also signal the company’s ambition: about $20 billion in revenue, $7 billion in specialty revenue, $10 billion in adjusted EBITDA, and ROIC above fifteen percent. Relative to 2025, that would imply roughly twenty-five percent revenue growth and about thirty-five percent EBITDA growth.

Nearer term, for 2026 management guided to revenue of $16.8 to $17.3 billion, adjusted EBITDA of $7.6 to $7.8 billion, and free cash flow of $2.15 to $2.45 billion.

X. Competitive Moats & Industry Dynamics

Equipment rental is one of those businesses where, if you’re the leader, the rules tend to bend in your favor over time. Not because the industry is easy—local competition is fierce—but because scale turns into real, compounding advantages.

Start with the most obvious moat: fleet and footprint. By 2025, United Rentals owned roughly five thousand classes of equipment with about $22.5 billion in original equipment cost. That fleet was spread across 1,768 locations globally—1,663 in North America, plus branches in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. No other company comes close to matching that combination of breadth, density, and sheer purchasing volume.

Behind United Rentals, the field drops off fast. Sunbelt Rentals, the number-two player and a subsidiary of London-listed Ashtead Group, held roughly eleven percent of the North American market with around 1,200 locations. Herc Rentals strengthened its number-three position after buying H&E Equipment Services in June 2025, bringing it to 613 locations and about $5.1 billion in pro forma revenue.

And then there’s everyone else. The top three players together control only about thirty percent of the market. The remaining seventy percent is still split among more than five thousand smaller operators.

That fragmentation cuts both ways. On one hand, it keeps pricing competitive in local markets. A small rental yard can still open with relatively modest capital—some equipment, some land, and a handful of people. On the other hand, serving the customers that matter most at the high end—national accounts that need consistent service across dozens of states, technology that ties together multiple jobsites, and a deep bench of specialty expertise—requires something closer to a multi-billion-dollar infrastructure build. Those barriers aren’t theoretical. They’re measured in decades, systems, and fleet.

Scale shows up most clearly in purchasing power. As the world’s largest buyer of construction equipment, United Rentals estimates it gets roughly five percent procurement savings versus smaller competitors. On a fleet with more than $22 billion in original cost, that adds up to well over a billion dollars of cumulative advantage—savings that can be reinvested into fleet quality, service, and technology, or simply kept as margin. Small competitors can’t “work harder” to close that gap. They have to get big first.

Technology has become the other major moat—and it’s not just about having an app. United Rentals’ Total Control platform gives customers real-time visibility into both rented and owned equipment across jobsites, handling everything from tracking and mapping to invoicing, scheduling deliveries and pickups, utilization analytics, telematics integration, and even emissions reporting tied to sustainability goals. By 2024, more than seventy-three percent of revenue was digitally engaged, with online revenue up twenty-two percent.

In 2025, the company added Smart Suggestions, a machine-learning feature that recommends equipment based on order history, jobsite data, and seasonality—cutting the time it takes customers to find and order what they need by twenty-seven percent. It also introduced Equipment Fit AR, an augmented reality feature that lets customers virtually place 3D models of equipment onto a jobsite using a mobile device.

By December 2025, United Rentals said it was scaling AI applications through a partnership with Amazon Web Services. It also ran United Academy, a digital training platform for operator safety certification, and launched ProBox OnDemand in 2024—an automated tool-tracking system using RFID so workers can check tools in and out without manual oversight, reducing theft and downtime.

These systems matter because they create switching costs. When your rental provider becomes the operating system for managing equipment across every jobsite, switching isn’t just “getting a better rate.” It’s ripping out workflows.

Data makes the lock-in even stronger. United Rentals’ Benchmarking Service draws on more than twenty years of proprietary information from millions of rental transactions, allowing customers to compare utilization and spending against industry averages. Smaller competitors can’t replicate that because they don’t have the history or the dataset. Once a customer starts using that kind of insight to run their fleet and control jobsite costs, the relationship gets deeply embedded.

United Rentals also avoids one of the classic risks of industrial businesses: customer concentration. No single customer accounts for even one percent of revenue. The top ten customers are only about four to five percent. That diversification means pricing power isn’t held hostage by a few giant buyers.

And then there’s the long-term tailwind pushing the entire industry: the steady shift from owning equipment to renting it. U.S. rental penetration reached fifty-seven percent in 2024—an all-time high—up from roughly forty percent in the early 2000s.

The logic is hard to argue with. Heavy equipment can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and it can lose a big chunk of its value quickly. Renting preserves capital. It provides access to newer, better-maintained gear. It reduces the need to hire mechanics. It lets contractors scale up and down with project demand. It keeps equipment off the balance sheet.

Every incremental point of rental penetration expands the market. And because United Rentals is built to say “yes” more often than anyone else—more locations, more fleet, more specialty capability, more technology—it tends to capture a disproportionate share of that expansion.

XI. Playbook: Lessons for Builders & Investors

The United Rentals story is a clean case study in how roll-ups actually work—when they create real value, when they don’t, and what separates a compounding machine from a pile of deals.

The first lesson is that not every industry is consolidatable. Roll-ups work best when a handful of conditions show up at the same time: the market is truly fragmented, the offering is relatively undifferentiated, scale creates real advantages in purchasing and technology, revenue is recurring or at least stable, and there’s a natural supply of sellers—often owner-operators looking for an exit.

Equipment rental checked all of those boxes.

Most roll-ups fail when one of those conditions is missing. Professional services is a classic trap: the “assets” are people, and after the deal closes, the best ones can walk out the door.

The second lesson is that the value isn’t created in buying businesses. It’s created after. Acquisitions are the easy part. Integration is the hard part—extracting synergies, standardizing the operation, and getting the combined company to run better than the pieces ever could on their own. United Rentals didn’t get that right by accident. It built a repeatable integration playbook across hundreds of acquisitions, and then kept refining it for decades.

That playbook was consistent: move acquired branches onto standardized systems quickly, centralize purchasing and finance, rationalize overlapping locations where it made sense, retain the best salespeople and branch managers, and run the whole thing against clear, comparable performance metrics.

The third lesson is about respecting capital intensity and setting real return thresholds. Equipment rental is a capital-hungry business by design. The fleet depreciates. Equipment gets used hard. And you have to keep deploying new capital just to stay competitive, let alone grow. In 2025 alone, gross rental capital expenditures exceeded four billion dollars.

So the scoreboard can’t just be growth or margins in isolation. The real question is whether the company earns attractive returns on all that invested capital. United Rentals’ return on invested capital has moved around over time, but it has generally stayed above its cost of capital—evidence that the company has been creating value, not just getting bigger.

The fourth lesson is the operating model: decentralized where speed and relationships matter, centralized where scale matters. At United Rentals, branch managers have real autonomy over local customer relationships, fleet allocation, and day-to-day execution. But they’re backed by centralized purchasing that can negotiate better economics, centralized technology that drives data and fleet optimization, and centralized finance that allocates capital across the network.

That blend—local empowerment with a strong central platform—is a familiar pattern in great multi-location operators, from Berkshire Hathaway to Danaher.

The final lesson is culture—because serial acquisitions aren’t just financial transactions. Every deal comes with its own identity, habits, and loyalties. Over hundreds of acquisitions, cultural drift can quietly break the machine.

United Rentals has tried to solve that by enforcing a consistent operating culture built around safety, customer service, and performance. Tools like the company’s Customer Focus Scorecard—which tracks nineteen metrics across five dimensions of service, including on-time delivery, off-rent pickup time, service response time, equipment availability, and billing dispute resolution—create a shared language that helps pull acquired businesses into one operating system.

XII. Bear vs. Bull Case & Future Outlook

The bull case for United Rentals starts with a simple idea: the work is there, and much of it is the kind of work that chews through rented equipment.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, signed in November 2021, set up $550 billion of new federal infrastructure spending through 2026—roads, bridges, water systems, broadband, and the grid. By early 2026, that money had been moving from engineering and permitting into actual dirt-moving and steel-setting. On the Q4 2025 earnings call, CFO Ted Grace said “the outlook for these so-called mega projects is very healthy,” and emphasized that the company didn’t believe it was in the “later innings” of the buildout.

Then there’s the next layer of demand: the clean-energy and reshoring boom. The Inflation Reduction Act adds roughly $100 billion per year in clean energy and advanced manufacturing investment, which shows up as new factories, new power infrastructure, and new industrial construction. The CHIPS and Science Act has also pushed capital into semiconductor fabrication plants—projects that are massive, long-duration, and equipment-intensive.

Put that together, and management sees what it describes as six to eight tailwinds at once: infrastructure, data centers, power generation, semiconductor manufacturing, advanced manufacturing and reshoring, and technology. The headline takeaway is that this isn’t one cycle; it’s a stack of multi-year build themes running in parallel.

The other pillar of the bull case is structural: the industry’s continued shift from owning equipment to renting it. U.S. rental penetration hit about fifty-seven percent in 2024, an all-time high. But that still leaves a lot of contractors—especially mid-sized ones—owning more fleet than they can keep consistently utilized. Every incremental shift toward rental expands the pie for the big renters, and United Rentals is built to capture an outsized share of that expansion.

You can see the demand shift in end markets too. The utility vertical alone grew from four percent to ten percent of United Rentals’ revenue in under a decade, driven by investment in the power grid. And the housing shortage in many U.S. cities provides a potential structural floor under residential construction activity, even if the pace moves up and down with mortgage rates.

The bear case is the thing you can never diversify away in this business: construction is cyclical.

Demand for rental equipment ultimately comes from construction and industrial activity, which is tied to interest rates, housing starts, commercial real estate investment, and government fiscal policy. A sustained downturn can take volume out of the system quickly. The 2008–2009 financial crisis is the reminder: United Rentals’ stock fell from the thirties to below five dollars. The company has more specialty exposure today, which can act as ballast, but general construction still drives most of the top line.

Rates and policy uncertainty add another layer of risk. Higher rates can tighten financing for contractors, weigh on residential construction, and raise the cost of capital across the rental industry. Tariffs are another potential pressure point: if equipment costs rise faster than rental rates can adjust, margins get squeezed.

And there are already signs worth watching. Adjusted EBITDA margin drifted down from 47.8 percent in 2023 to 46.7 percent in 2024 and 45.5 percent in 2025. That doesn’t automatically mean the model is breaking—management pointed to factors like the integration of lower-margin Yak assets and elevated fleet repositioning costs—but it’s a trend investors will keep an eye on because this business is so sensitive to operational efficiency.

Competition is also evolving. Herc Rentals’ acquisition of H&E Equipment Services created a stronger third player, with 613 branches and more than $5 billion in revenue. Sunbelt Rentals has kept expanding aggressively, including acquiring twenty-six businesses in its fiscal 2024 alone. United Rentals is still the dominant operator, but the landscape doesn’t stand still—and local competition remains intense.

If you step back and evaluate the moat frameworks, the picture is clear. Through the lens of Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers, United Rentals’ strongest power is scale economies: the larger fleet and denser network create structural cost advantages in purchasing, maintenance, logistics, and utilization that smaller competitors can’t match. It also has moderate-to-strong process power, built through decades of integration and fleet-management repetition—hard-won know-how embedded in how the company operates.

Switching costs are meaningful for large customers deeply integrated into Total Control, but much lower for small, transactional renters. Network effects exist, but they’re indirect: data advantages, better fleet sharing across branches, and better service consistency as the network grows. Branding matters, but it’s not the primary moat. Cornered resources are limited, though the decades-long dataset behind the Benchmarking Service acts like a quasi-unique asset. Counter-positioning doesn’t really apply here because United Rentals is the incumbent.

Porter’s Five Forces tells a similar story. New entrants can pop up locally with relative ease, but replicating United Rentals at national scale would require an extraordinary amount of capital—effectively a tens-of-billions-of-dollars problem. Supplier power is moderate, checked by United Rentals’ purchasing leverage. Buyer power is low because no customer is big enough to dictate terms. Substitutes are limited, especially as the secular trend continues moving from ownership toward rental. Rivalry is fierce at the branch level, but increasingly structured at the top, where the big players’ scale and discipline can create de facto pricing leadership over time.

For investors trying to track whether the story is staying on the rails, two KPIs tend to matter most.

First is fleet productivity—the composite measure that captures rental rates, utilization, and mix. When fleet productivity is sustainably positive, it usually means pricing discipline is holding and the network is allocating equipment well. When it turns negative, it can be an early sign of pricing pressure, weakening utilization, or both.

Second is specialty revenue as a percentage of total rental revenue. The shift from roughly fifteen percent of rental revenue to more than a third has been one of the biggest drivers of United Rentals’ mix improvement and differentiation. Continued progress toward management’s 2028 target of about $7 billion in specialty revenue would be a strong signal that the transformation is still compounding.

Looking forward, the runway is still long. Roughly seventy percent of the North American market remains in the hands of smaller operators, leaving plenty of room for consolidation. Internationally, United Rentals has been expanding in Europe, Australia, and New Zealand—markets with high rental penetration and broadly similar regulatory environments.

Whether the next decade is defined more by domestic roll-ups, international expansion, deeper specialty penetration, or some combination of all three, the bet is the same one the company has been making for years: with enough scale, enough operational discipline, and enough capital allocation restraint, United Rentals can keep turning a fragmented industry into a compounding machine.

XIII. Epilogue & Key Takeaways

United Rentals is a masterclass in what happens when an exceptional operator finds a fragmented industry with real scale advantages—and then executes with relentless discipline for decades. Brad Jacobs, the Brown dropout and classical pianist turned serial consolidator, later distilled his philosophy in a 2024 book titled "How to Make a Few Billion Dollars." The title is characteristically blunt. The thesis is just as direct: find a large, fragmented industry where scale creates real operational advantages, then consolidate it quickly and run it better than the independents ever could. United Rentals was his proof. He spotted the opening, built the foundation, and moved at a pace that turned a newborn company into the category leader almost immediately.

Michael Kneeland then became the steady hand the business needed. He guided United Rentals through the financial crisis, endured the Cerberus collapse as an independent company, and executed the RSC merger that locked in a structural advantage that still shapes the industry.

Matthew Flannery—who joined United Rentals in 1998 through its acquisition of Connecticut-based McClinch Equipment and rose from branch operations to district manager to regional vice president to COO to president to CEO in May 2019—has carried the machine forward. Under his watch, United Rentals has pushed harder into specialty, deepened its technology moat, and kept the same capital allocation discipline that has defined the modern era.

The compounding power of that discipline is the through-line of the entire story. Since 2012, organic growth, accretive acquisitions, margin expansion, and aggressive share repurchases have taken diluted earnings per share from under a dollar to nearly forty dollars. The company returned $2.4 billion to shareholders in 2025 alone and guided for roughly $2 billion of returns in 2026, backed by a new $5 billion share repurchase authorization.

This isn’t just a growth story. It’s a total shareholder return machine—built on a business model where operating leverage, network density, and scale economies reinforce each other year after year.

The most underappreciated part of the United Rentals story is where it happened: in a “boring” industry. Equipment rental doesn’t come with the glamour of technology, the mystique of biotech, or the cultural cachet of consumer brands. It’s heavy machinery, moved in and out of yards and onto jobsites, on time, every day.

The headquarters isn’t in Silicon Valley. It’s in Stamford, Connecticut. The product isn’t a sleek device or a viral app. It’s excavators, generators, and scissor lifts spread across a continent.

And yet, the stock has been a two-hundred-plus-bagger from its split-adjusted IPO price—outperforming the vast majority of companies in every corner of the market.

The lesson is simple: glamour has nothing to do with returns. What matters is the quality of the business model, the discipline of the management team, and how long the competitive advantage can last. United Rentals has all three.

As the company approaches its thirtieth year, it does so from a position of unmistakable leadership. It has the largest fleet in the world. Its branch network is roughly three times the size of its nearest competitor. Specialty has become a core growth engine. The balance sheet remains conservatively managed. And the organization keeps running the same playbook—tested, refined, and improved—year after year.

XIV. Recent News

In January 2025, United Rentals announced a deal to acquire H&E Equipment Services for about $4.8 billion—an acquisition that would have been the largest in company history. But the agreement included a 35-day go-shop window, and before it closed, Herc Holdings showed up with a higher offer: $104.59 per share in cash and stock.

United Rentals chose not to top it. On February 18, 2025, it terminated the deal, collected a $63.5 million breakup fee, and immediately restarted its share repurchase program. Herc went on to complete the H&E acquisition in June 2025, creating the third-largest equipment rental company with 613 locations.

Then came the latest scorecard. Full-year 2025 results, reported on January 28, 2026, showed $16.1 billion in total revenue, including $13.8 billion of rental revenue. Adjusted EBITDA was $7.3 billion, and free cash flow was $2.2 billion. During the year, the company opened around sixty specialty cold-start locations and returned $2.4 billion to shareholders through buybacks and dividends.

The quarter was bumpier. Q4 2025 adjusted EPS of $11.09 came in below consensus estimates of about $11.63, and the stock dropped roughly fifteen percent before partially recovering. Full-year adjusted EBITDA margin was 45.5 percent, continuing a step-down from 47.8 percent in 2023 and 46.7 percent in 2024. Management attributed some of the margin pressure to the integration of lower-margin Yak Access assets and the impact of a restructuring program.

For 2026, management guided to $16.8 to $17.3 billion of revenue, $7.6 to $7.8 billion of adjusted EBITDA, and $2.15 to $2.45 billion of free cash flow. The company raised its quarterly dividend by ten percent to $1.97 per share and announced a new $5 billion share repurchase authorization with no expiration date.

It also reiterated its 2028 aspirational targets: about $20 billion in revenue, $7 billion in specialty revenue, $10 billion in adjusted EBITDA, and return on invested capital above fifteen percent.

On the technology front, in December 2025 United Rentals said it was scaling artificial intelligence applications through a partnership with Amazon Web Services, reinforcing its push to use technology as a competitive edge. That same month, the company also acquired Direct Equipment.

By early February 2026, URI shares traded around $790, implying a market cap of roughly $50 billion and an enterprise value of about $57 billion. The stock had hit an all-time high of $1,017.86 on October 15, 2025, before pulling back after the Q4 earnings miss and broader market volatility.

XV. Links & References

- United Rentals SEC Filings (10-K Annual Reports, 10-Q Quarterly Reports): https://investors.unitedrentals.com/financials/sec-filings/default.aspx

- United Rentals Investor Presentations: https://investors.unitedrentals.com/events-and-presentations/default.aspx

- United Rentals Annual Reports: https://investors.unitedrentals.com/financials/annual-reports/default.aspx

- United Rentals Q4 2025 and Full Year 2025 Earnings Press Release (January 28, 2026)

- United Rentals Q4 2024 and Full Year 2024 Earnings Press Release (January 29, 2025)

- United Rentals Leadership Succession Plan Announcement (January 8, 2019)

- United Rentals–Cerberus Merger Agreement Announcement (July 23, 2007)

- Delaware Chancery Court Ruling on Cerberus–United Rentals (December 21, 2007)

- American Rental Association (ARA) industry reports and market data

- Forbes: Silvia Sansoni, “The Earth Mover” (June 1998) on Brad Jacobs and United Rentals’ founding

- Forbes: Antoine Gara, “Better Than Amazon? How Bradley Jacobs Turned a $63M Bet Into a $12 Billion Transportation Empire” (April 2018)

- Wall Street Journal: Steven Lipin on the equipment rental consolidation thesis

- Brad Jacobs, How to Make a Few Billion Dollars (2024)

- David Senra Podcast: Brad Jacobs interview on QXO, XPO, United Rentals, and United Waste (November 2025)

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music