Venture Global: The Disruptors Who Built America's LNG Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Thesis

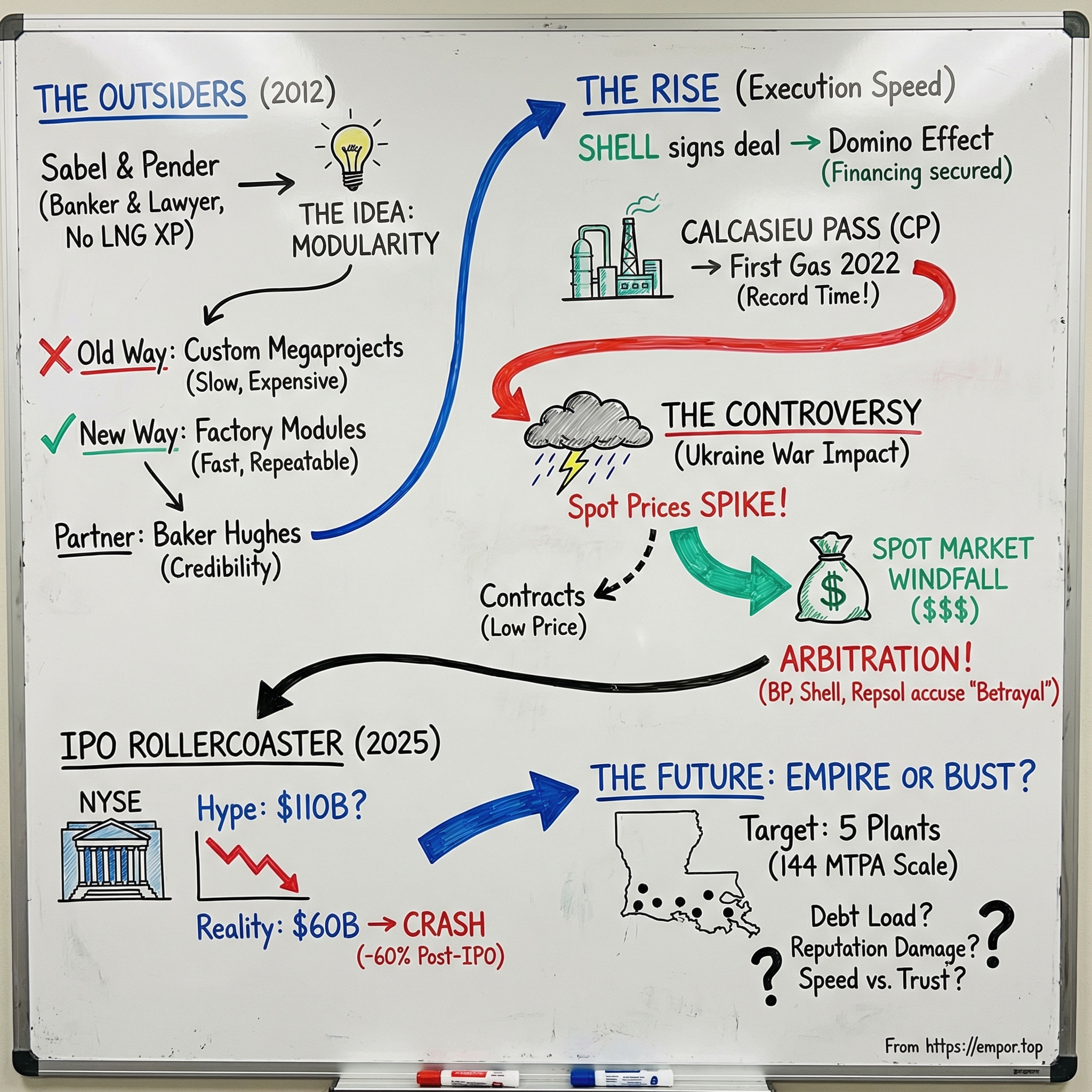

On a frigid January morning in 2025, Venture Global stepped onto the New York Stock Exchange. The stock opened at $25 a share, and in an instant it looked like one of the biggest energy IPOs in a decade. The headline was almost too clean: two men who’d never worked a day in liquefied natural gas had built a company the market valued at around $60 billion. On paper, Michael Sabel and Robert Pender each walked away from that first day with fortunes of roughly $24 billion.

And then the story turned.

Not long after the celebration, Venture Global’s shares plunged—down more than 60%—wiping out roughly $39 billion in market value. At the same time, six major customers, including BP, Shell, and Repsol, filed arbitration claims. The accusation: Venture Global had prioritized selling LNG into the high-priced spot market instead of delivering contracted volumes under long-term deals. The same outsider mindset that helped them break into a fortress-like industry was now being framed as something darker—sharp-elbowed, opportunistic, maybe even unlawful.

Still, it’s hard to overstate how improbable Venture Global’s rise has been. In just over a decade, it went from nothing to the second-largest LNG exporter in the United States, behind only Cheniere. Along Louisiana’s Gulf Coast, the company has built—and is building—five sprawling LNG facilities, with expected peak capacity of nearly 144 million tonnes per year. In practical terms, that’s energy on the scale of nations.

So here’s the question this story revolves around: how did two total industry outsiders—an investment banker and a Big Law partner—build one of the most valuable, and most controversial, energy companies in America?

The answer isn’t just “they got lucky.” It’s a mix of a radical construction idea, a perfectly timed wave in global energy markets, and a set of business decisions that some partners now describe as betrayal and management describes as standard practice. Venture Global didn’t merely build LNG plants. They challenged the unwritten rules of how LNG is supposed to get built, financed, and sold.

And that’s what makes this such a useful story—especially if you care about how real wealth gets created in capital-intensive industries. Because the trade-offs are never abstract. Move faster, and you’ll step on toes. Optimize profits, and you may burn relationships you need for decades. Disrupt the incumbents, and eventually you inherit the responsibilities of being one.

Whether Venture Global ends up remembered as visionary or reckless depends on what happens next. But to understand how we got here, we have to start at the beginning—back when this was just two guys with no LNG pedigree, a big idea, and the nerve to try.

II. The Unlikely Founders: Sabel & Pender's Origin Story

In the summer of 2012, a rented Chevy Suburban rolled through the small towns and back roads of East Texas. Bob Pender was driving. He was in his sixties, a former Big Law partner who’d spent decades advising Fortune 500 companies on complex transactions. In the passenger seat was Mike Sabel, an investment banker with a worn pitch deck, a relentless cadence, and a résumé that started with an unusual line: he’d dropped out of the University of Michigan and built his career in commercial finance anyway.

They weren’t touring oilfields for fun. They were going door-to-door looking for someone—anyone—willing to fund an audacious plan: build a liquefied natural gas export facility.

Most meetings ended the same way. Polite smiles. Hard skepticism. Then the punchline: You’ve never built anything. You don’t know LNG. Thanks for coming.

They’d nod, gather their papers, get back in the Suburban, and drive to the next pitch. They did it for months.

Pender’s route to that passenger list of investor meetings was anything but direct. Early in his career, he served as a White House law clerk during the Carter administration—an era when energy wasn’t an abstract policy debate, it was lived reality. The Iranian Revolution, gas lines, a country rattled by price shocks and scarcity. From there, Pender built a long career in Washington, DC as a partner at a major firm, specializing in big, messy infrastructure transactions. He knew how the machinery of permitting and regulation worked. He knew how power flowed through institutions. But like he’d later admit, he’d always been the adviser—not the one actually breaking ground.

Sabel, by contrast, had the profile of someone who lived inside spreadsheets and term sheets. After leaving Michigan without a degree, he bounced through investment banking and commercial finance, developing a reputation for stamina and deal instinct. The kind of person who would call at odd hours because he’d found a better structure, a cleaner angle, a way to make a difficult project financeable. He didn’t have an engineering pedigree. What he had was a deep feel for how capital moves—and what it takes to persuade it.

Their partnership really took shape around a failure.

In 2009, the two tried to build a coal power plant in Sri Lanka. It was years of effort that went nowhere—political instability, permitting issues, financing friction, and the slow grind of reality. For most people, that’s the moment you retreat to your day job and treat the whole thing as an expensive lesson.

They did the opposite. They started asking what they’d missed, and what they could do differently next time.

That’s how LNG entered the picture. In looking at energy options for developing countries, they got fixated on a deceptively simple question: how could a place like Haiti import smaller amounts of natural gas? Traditional LNG infrastructure wasn’t built for that. The whole industry assumed scale—massive plants, massive ships, massive contracts with massive buyers. If you weren’t a supermajor or a national utility, you didn’t belong in the conversation.

But that constraint—the industry’s obsession with bigness—started to look less like a law of nature and more like an opening.

By 2012, the shale revolution had already flipped the U.S. energy equation. Natural gas was suddenly abundant and cheap at home, and much more valuable overseas. The gap was real, and the business model was obvious: buy low in the U.S., liquefy it, ship it, sell high abroad. The catch was that “liquefy it” sat behind one of the hardest engineering and financing gates in the entire industrial economy.

LNG export terminals were famous for a reason. They were some of the most complex facilities humans build—cryogenic plants that chill gas to roughly minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit so it becomes a liquid compact enough to ship. They took years. They consumed billions. They demanded specialized expertise, a small army of contractors, and the kind of credibility that usually comes from being Shell, Exxon, or a sovereign wealth fund.

Two outsiders in a rented SUV had no business playing this game.

And yet, those outsiders had one advantage the insiders didn’t: they weren’t burdened by the industry’s inherited assumptions. When Sabel and Pender looked at the standard LNG playbook—custom megaprojects assembled on-site over many years—they didn’t see inevitability. They saw a system that looked strangely outdated for an industry that claimed to be cutting-edge.

They asked the kinds of questions that get you laughed out of rooms—until they don’t. Why did LNG trains have to be so big? Why were these plants essentially one-off prototypes every time? Why couldn’t major components be built in factories, where work is faster, repeatable, and easier to control? Why did construction have to take a decade?

The answers tended to be a shrug dressed up as wisdom: because that’s how it’s always been done.

For two people who’d already tried the “conventional” route and watched it collapse in Sri Lanka, that wasn’t a principle. It was a challenge.

Their partnership worked because the fit was clean. Pender brought legal sophistication and Washington fluency: how to navigate federal permitting, how to structure agreements that could survive regulatory scrutiny, how to think in policy timelines. Sabel brought capital markets instincts and commercial intensity: how to sell the vision, how to finance it, how to keep momentum when everyone tells you the obvious answer is no.

By 2013, they incorporated Venture Global and committed to the long, bruising process of turning their contrarian idea into something real. They were still underfunded. Still dismissed. Still outsiders.

But they now had the one thing that matters most at the beginning: a different way of seeing the problem—and the stubbornness to keep driving until someone else could see it too.

III. The Modular Revolution: Reimagining LNG Infrastructure

To understand what Venture Global disrupted, you first have to understand what LNG infrastructure normally looks like. These are engineering marvels—some of the most complex industrial projects humans routinely attempt.

Start with the basic unit: an LNG “train,” the chain of equipment that takes natural gas in and liquefies it. A traditional train is enormous, filled with hundreds of specialized components that have to work in lockstep while handling cryogenic temperatures cold enough to make ordinary materials brittle. Gas goes in at ambient temperature and comes out as a super-cooled liquid that takes up roughly 600 times less space—small enough to ship across oceans. Making that happen means massive compressors, intricate heat exchangers, and systems that live right at the edge of what materials and engineering tolerances allow.

For decades, the LNG world ran on a set of assumptions that felt like laws of physics. Bigger trains meant better economics. Every plant was custom-designed for its site. Construction happened in place, with thousands of workers assembling pieces sourced from all over the world. And timelines were measured in nearly a decade—often eight to ten years from idea to first gas—while budgets routinely stretched into the tens of billions.

That’s why the industry belonged to the supermajors: ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, TotalEnergies. They had the engineering benches, the balance sheets, and the institutional muscle to survive a project where a single delay could ripple for years. New entrants weren’t just rare. The whole system seemed built to prevent them.

Sabel’s breakthrough came from a question that sounded almost naive: why did LNG have to be built like a one-off megaproject every time? What if you could build an export terminal the way other complex industrial products get built—by fabricating major pieces in factories, then assembling them on-site?

Modular construction itself wasn’t radical; plenty of industries use it. What made this idea heretical was applying it to LNG liquefaction, where extreme cold, tight tolerances, and operational complexity had long been used as the argument for custom, on-site integration. The conventional wisdom said you needed massive trains for efficient performance, and you needed bespoke engineering to make the whole system behave.

Sabel and Pender took the opposite view. Instead of one giant train, what if you ran many smaller ones in parallel? Instead of building a bespoke machine on a muddy jobsite over many years, what if you manufactured repeatable units in controlled conditions and then installed them quickly?

Of course, an idea like that lives or dies on one thing: whether a serious engineering partner is willing to stake their name on it. Venture Global found that partner in Baker Hughes, one of the world’s biggest oilfield services companies. Baker Hughes had developed a packaged, modular liquefaction concept—known as System One—designed to be built and tested in factories and then shipped for installation.

That partnership changed Venture Global from an outsider pitch into something financeable. Baker Hughes brought credibility, manufacturing capability, and deep experience with complex equipment. Venture Global brought what the LNG establishment often lacked: a customer willing to bet on modularity at meaningful scale.

The architecture that emerged was genuinely different. Rather than a handful of giant trains, Venture Global’s plants would use dozens of smaller modular units working in parallel. Each unit could be fabricated and tested at Baker Hughes facilities, then delivered to Louisiana for installation. Standardization meant repetition. Repetition meant learning curves. And learning curves meant speed.

A useful analogy is the difference between building a custom house and using prefabrication. Custom construction keeps the hardest work on-site, where weather, labor constraints, and unexpected conditions slow everything down. Prefab shifts complexity into a factory, where quality control is tighter and production becomes more predictable.

Modular LNG offered the same set of theoretical advantages. Factory work could happen while the site was being prepared, compressing the schedule. Quality was easier to manage under roof than in the Gulf Coast rain. Standard designs reduced surprise engineering. And using many units gave the system resilience: a problem with one module didn’t have to become a total-plant crisis. It also reduced the project’s exposure to the kinds of weather delays that can wreck timelines along the coast.

But when Venture Global announced plans for its first facility, the reaction was not awe. It was disbelief. In 2015, BloombergNEF looked at the combination—no operating history, limited resources, and an unproven technical approach—and called the project “highly unlikely” to be built. That wasn’t a hot take at the time. It was the consensus.

What the skeptics missed was that modular construction didn’t just change how you built an LNG plant. It changed the risk profile of the entire business. Traditional LNG megaprojects concentrate risk into a small number of massive, tightly coupled systems. You commit huge sums long before revenue arrives, and a single failure can hold up everything. Venture Global’s approach spread risk across many smaller units, and in theory made problems more containable.

It also reshaped the capital curve. Instead of pouring vast amounts in upfront and waiting years for the first dollar back, modular construction promised a faster path to first production. For a startup without a supermajor balance sheet, that wasn’t a nice-to-have. It was the difference between “possible” and “dead on arrival.”

And above all, it offered speed. In an industry where ten-year timelines were normal, Venture Global aimed for first gas in well under five years from the start of construction. Speed would become a core part of the Venture Global identity—an advantage that powered their rise, and later, a source of controversy.

The technical bet—partnering with Baker Hughes and going modular—would prove to be directionally right. But technology alone doesn’t build an LNG exporter. Next came the harder part: convincing customers to commit, financiers to fund, and regulators to permit a new kind of LNG company—before it had ever shipped a single cargo.

IV. Building the Business: From Zero to First Gas (2013–2022)

By the summer of 2016, Venture Global had something most first-time LNG developers never get: a real shot at legitimacy.

After years of pitching and getting politely shown the door, Sabel and Pender found themselves sitting across from Royal Dutch Shell—one of the biggest names in global energy, and one of the toughest buyers in LNG. Shell had seen every kind of export-terminal dream. Most of them never got past the PowerPoint stage.

This one did.

Shell signed a 20-year agreement to buy LNG from Venture Global’s planned Calcasieu Pass facility in Louisiana. That signature did more than secure future revenue. It told the entire market that a supermajor with deep technical benches was willing to take Venture Global seriously.

Once Shell was in, the dominoes started to fall. Venture Global soon added more long-term agreements—with BP, Edison, Sinopec, and others. Each deal made the next conversation easier. The pitch basically became: you don’t have to believe in us on faith anymore. Look who already does.

Those contracts weren’t just commercial wins; they were the financing engine. An LNG export facility costs billions to build, and lenders don’t fund billions on vibes. They want predictable cash flows. Long-term purchase agreements with blue-chip counterparties are how LNG projects get “bankable.” So Venture Global followed the industry’s standard sequence—sign customers first, then raise project finance, then build—but executed it with unusual speed for a brand-new entrant.

Louisiana, meanwhile, was an unusually clean fit. It had the pipelines, the industrial workforce, and Gulf access LNG requires. It also had a political climate that wanted energy development—and the jobs and tax base that came with it. For Venture Global, which needed to move fast and avoid getting bogged down, that mattered.

Calcasieu Pass, in Cameron Parish near the Texas border, became the company’s first big bet. The site offered access to abundant gas supply and a ship channel that could handle large LNG carriers headed for overseas markets.

Then came the hard part: permitting.

Building an LNG export terminal in the U.S. means navigating a multi-agency maze. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission oversees the facility itself. The Department of Energy controls export authorizations. There are environmental reviews, public comment periods, and the ever-present risk of lawsuits and delays.

Venture Global moved through that process faster than many expected. Some of that was execution—this is where Pender’s Washington experience was a real edge. Some of it was timing, as U.S. policy was becoming more open to LNG exports across administrations. And some of it was local alignment: Louisiana’s leadership treated LNG as an economic priority.

With permits in hand, construction at Calcasieu Pass ramped in 2019, and the modular theory met real-world conditions. Baker Hughes fabricated liquefaction units while site work advanced in Louisiana, compressing the schedule. The project still faced the usual Gulf Coast realities—storms, flooding, labor constraints, and supply-chain issues—but the modular approach was designed for exactly this kind of unpredictability. When one piece slipped, the whole project didn’t necessarily stop.

Then 2020 arrived and tried to break every construction schedule on Earth.

COVID-19 disrupted global supply chains, forced new jobsite safety protocols, and threw energy markets into uncertainty. Plenty of big projects slowed down or died. Venture Global kept pushing.

That period also surfaced something foundational about how the company operated. In 2020, the founders reshuffled leadership and Sabel became sole CEO. The organization moved with a kind of urgency that people around it would later describe as relentless—results-first, tolerance-for-delay near zero. It got things done. It also created friction.

In January 2022, Calcasieu Pass produced its first LNG.

For Venture Global, it was the moment the whole bet finally clicked into place. From the start of construction to first production took roughly three years—dramatically faster than the industry’s traditional timeline. The payoff wasn’t just pride. Faster construction meant less time with capital tied up, less exposure to shifting markets while waiting for completion, and an earlier start to real revenue.

But first gas isn’t the finish line in LNG. It’s the handoff from building to operating—and those are different sports. Running a liquefaction facility means producing cargoes reliably, maintaining sensitive equipment, coordinating shipping logistics, and managing downtime without breaking commitments. For a company that had never operated anything at this scale, that transition was always going to be the next test.

Still, by early 2022, what they’d pulled off was undeniable. Two outsiders had taken an unconventional construction model, signed long-term contracts with some of the biggest energy buyers in the world, financed the build, navigated U.S. permitting, and brought a major export facility online—fast.

And yet, the same intensity that made all of that possible was about to become the problem. Because the customers who helped fund Venture Global’s rise were about to learn, in the most painful way, what kind of partner they’d actually signed up with.

V. The Customer Controversy: Arbitration Drama

In the world of long-term LNG contracts, every word is negotiated like it might someday end up on a courtroom projector. Because it often does. And in Venture Global’s case, one phrase that once sounded like harmless engineering jargon has become the center of a fight that now hangs over the entire company: “commissioning cargoes.”

When an LNG facility starts up, it doesn’t flip from zero to fully commercial overnight. There’s a ramp-up period where operators test equipment, tune processes, and work through the inevitable surprises of commissioning a complex, cryogenic plant. LNG produced during that phase is commonly sold by the developer—often into the spot market—before the facility is declared fully operational and obligated to deliver contracted cargoes on schedule. That practice isn’t unusual.

What was unusual was how long Venture Global kept Calcasieu Pass in that commissioning category—and how perfectly that stretched timeline lined up with the hottest LNG market in modern history.

Calcasieu Pass began producing LNG in January 2022. By most outward measures, the plant worked: it produced meaningful volumes and showed that the modular concept could operate at scale. But Venture Global continued to treat those cargoes as commissioning cargoes rather than commercial deliveries that would flow to its long-term customers under their contracts.

Then geopolitics poured gasoline on the market. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sent Europe scrambling to replace Russian pipeline gas, almost overnight. Spot LNG prices surged to levels far above what long-term contracts typically pay. In that environment, every cargo that went to the spot market instead of a contract buyer wasn’t just incremental revenue—it was a windfall.

Venture Global, suddenly, was sitting on exactly the kind of asset everyone in global energy wanted, precisely when they wanted it most. Bloomberg analysis later estimated the company earned about $7.8 billion from spot sales in 2023 alone. For a company that had only recently moved from “unproven developer” to “actual exporter,” that number landed like a thunderclap.

For the customers who had signed 20-year agreements—often at prices far below the new spot market—the optics were brutal. They believed they’d paid for certainty: long-term supply, reliably delivered, regardless of market chaos. Instead, they watched Venture Global sell large volumes at the high-priced spot market while their own contracted cargoes didn’t arrive. Their argument, in plain terms, was that the company used a technical startup label—commissioning—to delay its obligations and capture extraordinary profits.

Eventually, six customers filed contract claims: BP, Shell, Repsol SA, Orlen, Galp Energia, and Edison SpA. They alleged self-dealing and breach of contract. The core claim was consistent across the disputes: Calcasieu Pass was capable of moving into normal commercial operations sooner than Venture Global acknowledged, and the company deliberately prolonged commissioning to keep selling into the spot market.

The precise dollar amounts in arbitration aren’t fully public, but the stakes are widely understood to be enormous. And the bigger risk for Venture Global may not be the final awards. It’s that these are exactly the counterparties LNG developers need—deep-pocketed, repeat buyers who sign multi-decade deals that make multi-billion-dollar projects financeable. These relationships aren’t a nice-to-have. They are the business model.

Venture Global has pushed back hard. The company’s defense is that commissioning provisions were standard, negotiated language that customers agreed to. It argues the extended commissioning period reflected real technical and operational issues, not a commercial choice. And it points out—fairly—that the market shock after Ukraine wasn’t something contracts written years earlier could fully contemplate.

There’s truth in that. Commissioning complex plants often takes longer than anyone wants. Contract language around commissioning can be fuzzy. And these buyers weren’t naïve—they knew they were signing with a first-time operator running an unconventional design. Some level of startup friction was always part of the bargain.

But critics see something else in how this played out: a glimpse of Venture Global’s operating philosophy. When the choice was between maximizing near-term economics and preserving the spirit of long-term customer relationships, the company appeared to choose economics. In LNG, where contracts run for decades and reputations travel fast, that can be a costly trade.

And the damage doesn’t stop with the six claimants. Every future buyer evaluating a new deal now has to ask uncomfortable questions. If another market shock hits—if prices spike, or supply tightens—will Venture Global behave like a long-term partner, or like a trader with a legal strategy?

Those questions matter because Venture Global isn’t done building. It has multiple facilities planned or under construction along the Gulf Coast, and financing that expansion depends on signing more long-term customer commitments. Arbitration headlines make that harder. Even when lenders and buyers like the assets, they don’t like uncertainty—especially uncertainty tied to contract performance.

Meanwhile, arbitration takes time. These proceedings can drag on for years, creating an overhang that seeps into everything: customer negotiations, investor confidence, and the company’s stock. Each update becomes a new datapoint for the market to argue over, without any clean resolution.

Management has tried to project control—emphasizing that it intends to resolve disputes and maintain relationships. But the underlying tension remains. The same aggressive, speed-first posture that helped Venture Global break into LNG is now colliding with the industry’s most unforgiving reality: once you sign a 20-year deal, you’re not just building a plant. You’re building trust that has to survive every market cycle.

And that sets up the next act of the story. Because this controversy didn’t just create legal risk. It changed how the public markets saw Venture Global—right as the company was preparing to sell itself to investors at one of the biggest valuations in energy.

VI. The IPO Saga: From $110B Dreams to Reality Check

Wall Street loves a clean, cinematic narrative: two outsiders crash an entrenched industry, rewrite the engineering playbook, and ride a geopolitical wave into explosive growth. So when Venture Global started seriously exploring an IPO in 2024, bankers smelled something rare in energy: a story that could sell.

In those early conversations, the price tag floated was enormous. Reports suggested the company and its advisers considered a valuation as high as $110 billion—territory that would have put Venture Global in the same sentence as long-established U.S. energy giants. The pitch was straightforward: global LNG demand was growing, modular construction was a structural edge, and Venture Global was building capacity into a market that looked chronically tight.

Then the complications that had been manageable in private became unavoidable in public.

The customer arbitrations didn’t just “exist” anymore; they became central. Investors doing diligence weren’t only underwriting LNG demand. They were underwriting whether Venture Global’s customers would keep trusting it, whether the company could consistently operate at scale, and what the disputes might mean for future cash flows. Governance questions came along for the ride. As that scrutiny intensified, the valuation expectations started to come down to earth.

By January 2025, when the IPO finally priced, you could see that recalibration in the deal itself. Venture Global sold 70 million shares at $25 each—well below the earlier indicated range of $40 to $46—raising about $1.75 billion. The implied valuation, roughly $60 billion, was still staggering for a company that had only begun producing LNG in 2022. But it was also a clear step down from the $110 billion dream.

Even with that haircut, the offering landed as a milestone: the largest oil and gas IPO in a decade, and the first major IPO of the second Trump administration. In a little over twelve years, Sabel and Pender had gone from pitching in a rented Suburban to ringing the bell at the NYSE.

But the public-market honeymoon didn’t last.

In the weeks after the offering, the stock sank hard—dropping from $25 to below $10. More than 60% of the value evaporated, erasing roughly $39 billion in market cap. On paper, the founders’ IPO-day fortunes—previously estimated around $24 billion each—shrunk dramatically as the market repriced the story.

The selloff had more than one cause. The arbitrations hung over the stock like a cloud that wouldn’t move, and every new headline reminded investors that these weren’t abstract disagreements—they were disputes with exactly the counterparties the company needed for decades. At the same time, investors worried about energy-market volatility and the possibility that LNG supply could eventually catch up, or even overshoot. And once momentum turned, early IPO buyers selling quickly only added more pressure.

What really hurt, though, was the narrative that formed around it: that Venture Global had tried to squeeze its IPO into a brief window of optimism, and that the thesis started to fray as the market dug deeper into operational realities and customer conflict. Fair or not, it echoed the criticism in the arbitrations themselves—the idea that Venture Global optimized for economics and timing, even if it strained the relationships on the other side of the table.

The episode underscored a simple truth about going public: it’s where private-company confidence meets public-company interrogation. Issues you can contain behind closed doors—contract disputes, governance concerns, reputational questions—don’t stay contained once analysts, journalists, and thousands of shareholders are watching.

For Venture Global, the IPO did what IPOs do: it opened the door to public capital. But it also came with immediate costs. A lower, volatile stock price makes future equity financing more painful. It complicates employee compensation when equity is a major part of the package. And it gives prospective customers one more reason to hesitate before signing a long-term commitment.

Meanwhile, the company’s control structure didn’t change. Sabel and Pender retained control through a dual-class setup: they own all the Class B shares through a holding company, split 50/50. That means they can keep steering the ship regardless of what the stock does day to day—but it also means public shareholders have limited leverage over strategy and governance, even if they disagree with how the company plays the game.

In the end, the IPO didn’t erase Venture Global’s operational achievement. It reframed it. Building LNG facilities quickly is one kind of credibility. Public markets demand another. And Venture Global was about to learn, in real time, how expensive that second kind can be.

VII. The Business Model: Infrastructure as Competitive Advantage

Along the Louisiana Gulf Coast—where marshland gives way to ship channels and steel—Venture Global has been trying to do something that sounds almost absurd until you see it: build an LNG empire, five terminals deep, clustered across Cameron and Plaquemines parishes.

If they finish what they’ve started, the scale won’t just be big. It will be nation-sized. Venture Global expects the five facilities to reach peak production of about 143.8 million tonnes per year. For context, total U.S. LNG export capacity in 2023 was around 90 million tonnes annually. In other words, Venture Global alone is building more capacity than the entire country was operating just a couple years ago.

Calcasieu Pass proved the first point: modular LNG could work in the real world. Plaquemines LNG proved the second: it could be repeated. Plaquemines reached first production in December 2024, and with that, Venture Global’s model started to look less like a one-off experiment and more like a factory line. The next wave—CP2, CP3, and Delta LNG—sat in various stages of development and permitting.

Underneath the construction story is a business model that’s supposed to feel boring, even if the facilities aren’t. LNG projects are typically financed and run on long-term contracts—often 20 years—that give lenders and investors something they can underwrite. Many of these agreements are take-or-pay: customers either lift their contracted volumes or pay anyway. That structure is the foundation of project finance. It’s how you borrow billions against a plant that doesn’t exist yet.

But Venture Global’s version of that model has a second engine: an unusually strong appetite for spot-market exposure. The commissioning cargo dispute wasn’t just legal drama; it was a window into how the company seems to think about optionality. When the market got tight and spot prices spiked, Venture Global sold aggressively into those prices rather than transitioning quickly into contracted deliveries. That choice created enormous short-term gains—and an equally enormous question mark around how “firm” firm supply really is.

Financially, you can see both the opportunity and the volatility. In 2024, Venture Global reported about $5 billion in revenue and $1.5 billion in net income—remarkable for a company whose first facility only began producing LNG in early 2022. Then in the second quarter of 2025, results accelerated again: revenue nearly tripled to $3.1 billion and operating income rose 186% versus the prior-year quarter.

This is the operating leverage that makes LNG so alluring. Once the plant is built, the day-to-day cost structure isn’t the hard part. You have feed gas, fuel and power for compression, maintenance, staffing. But the real step-change is capacity coming online. When volumes ramp and pricing is favorable, revenue can surge far faster than costs.

The problem is that the leverage runs both ways—and it’s funded with breathtaking amounts of capital. Venture Global has disclosed plans to spend more than $100 billion in total capex to complete the five-facility buildout. That’s not “big for an upstart.” That’s among the largest private infrastructure bets in modern U.S. history.

To pull that off, the company needs continuous access to capital. Most of the construction money comes from project finance debt, backed by long-term contracts and the facilities themselves. The public listing adds another tool: issuing equity. But the post-IPO stock collapse changed that math. When your share price is down dramatically, raising equity becomes more expensive and more dilutive than anyone hoped when they were modeling the IPO roadshow.

Louisiana is central to this strategy—and it cuts both ways. The advantages are obvious: proximity makes it easier to share infrastructure, reuse suppliers, and develop a repeatable operating playbook. The company can build deeper relationships with local contractors, regulators, and political leadership. A concentrated footprint also makes workforce development more practical; you’re building a durable labor ecosystem in one place.

The risks are just as obvious, and they’re physical. A major hurricane can hit multiple assets at once. A local regulatory shift doesn’t affect one facility; it affects the whole portfolio. If there’s a labor crunch, it’s your entire buildout that slows. Venture Global has essentially tied its future to one coastline.

If they can finish construction on schedule and repair customer relationships, the competitive position could be extremely hard to copy. LNG is not software. The best sites are scarce. Permitting takes years. And customer relationships aren’t won with pricing alone; they’re built over decades of performance. A rival trying to match Venture Global’s scale would be starting from behind and would likely need many years to catch up.

So for anyone trying to understand whether this model really works, the scoreboard is simple. First: construction execution—are the projects finishing on time and on budget, and does modularity keep delivering the speed advantage? Second: commercial credibility—do the arbitrations get resolved, and can Venture Global still sign new long-term deals with serious counterparties?

Because in LNG, concrete and steel create capacity. But contracts create companies.

VIII. The Macro Thesis: Energy Transition & Geopolitics

In conference rooms from Berlin to Beijing, energy ministers are running into the same stubborn problem: the transition away from fossil fuels is harder in practice than it looks on a slide deck. Solar and wind have scaled quickly, but power grids still need something dependable when the wind dies or clouds roll in. Batteries keep getting better, but they’re not yet a universal answer for multi-day gaps. And across much of the developing world, coal remains the default—cheap, available, and brutally effective at wrecking air quality and raising emissions.

That’s the opening LNG has squeezed into.

As a power-generation fuel, natural gas emits roughly half the carbon dioxide of coal and produces far less local air pollution. For countries trying to clean up without risking blackouts—or slowing growth—LNG can look like the least-bad option. Not a final destination, but a workable path between today’s reality and tomorrow’s ambition.

The demand case starts in Asia. Shell has forecast global LNG demand growing by about 50% through 2040, with much of that driven by Asian markets. China, even while investing heavily in renewables, continues importing natural gas as a way to displace coal. India’s combination of fast growth and severe air-quality pressures makes it a major potential driver as well. And across Southeast Asia—Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines—governments are building LNG import terminals to fuel industrialization.

Europe, meanwhile, changed almost overnight. The pivot away from Russian gas turned the continent from a stable, mostly pipeline-supplied market into an urgent LNG buyer. Germany, most prominently, scrambled to add import capacity after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That infrastructure—built at huge cost and unusual speed—creates long-term pull for seaborne LNG that largely didn’t exist before 2022.

Then there’s the U.S. policy layer. Under the second Trump administration, a declared “national energy emergency” prioritized fossil fuel exports, and the Department of Energy resumed approving export permits that had been paused under the Biden administration. For Venture Global and other U.S. developers, that meant fewer regulatory headwinds—at least for as long as that policy stance held.

But LNG is never just about engineering and contracts. It’s about the world staying the same long enough for those contracts to matter. And the very geopolitical forces that made LNG indispensable can also fade or flip. A settlement that restores some Russian gas flows to Europe could cool demand and prices. A weaker-than-expected Chinese economy could undercut the biggest growth engine. A faster-than-expected renewables buildout could shorten the lifespan of the “bridge fuel” thesis.

Competition is also catching up. Qatar is expanding aggressively. Australian projects continue to ramp. New supply is emerging in Africa, from Mozambique to Senegal. In the U.S., incumbents and peers—Cheniere, Sempra, and others—have their own growth plans. The market tightness that has supported strong pricing is not guaranteed to last.

And over all of it sits the climate debate. Natural gas is cleaner than coal, but it still emits carbon. Methane leakage across the LNG value chain—from production to liquefaction to shipping to regasification—can erode the advantage. Environmental advocates argue that building LNG terminals locks in decades of fossil fuel dependence at the moment when rapid decarbonization is most urgent.

That’s why the bridge-fuel framing matters so much. If gas is a bridge, how long is it supposed to be—ten years, twenty, fifty? The answer determines whether the plants being built today run as cash machines for their full lives, or become stranded assets before they’re fully depreciated.

For Venture Global, the macro picture has recently offered strong tailwinds: rising global demand, supportive U.S. policy, and the structural advantages of Gulf Coast export economics. But those tailwinds can shift fast. The same volatility that created Venture Global’s opportunity—wars, price spikes, sudden policy changes—can just as easily compress margins, chill demand, or slam the regulatory window shut.

In other words, the macro thesis that powers the bull case can become the macro thesis for the bear case with very little warning.

IX. Power Dynamics & Governance Evolution

Back when Venture Global was just two men in a rented car, governance was simple. Sabel and Pender decided. They split the work by instinct and by advantage. And when something didn’t work, they rewired the plan on the fly.

That kind of informal control doesn’t scale cleanly to thousands of employees, multibillion-dollar construction sites, and a company that public markets try to value in the tens of billions. So as Venture Global grew, the founders formalized the leadership structure—but they did it in a way that preserved the one thing they clearly cared about most: keeping the steering wheel.

In 2020, Venture Global reorganized leadership. Sabel became sole CEO, while Pender moved into the Executive Co-Chairman role. It wasn’t hard to see the logic. Sabel’s intensity and commercial focus made him the obvious choice to run the day-to-day machine: construction schedules, operations, customers, capital. Pender, with his legal background and Washington experience, was better positioned to play defense and offense on the regulatory and governance front—exactly the kind of work that gets more important as a company becomes larger and more visible.

But the real story of power at Venture Global isn’t the org chart. It’s the cap table.

Sabel and Pender own all of the company’s Class B shares through a holding company, split 50/50. Those Class B shares carry supervoting rights, which means the founders control the company even if the public markets sour on the stock. Dual-class structures are common in Silicon Valley. In energy, they’re rarer—and they send a clear signal: this is not a company that intends to be governed by consensus.

At the IPO, Sabel, Pender, and employees collectively held just over 90% of the economic interest. The public float was relatively small, which limits liquidity and makes it harder for large institutions to build meaningful positions. And while the founders’ paper fortunes—about $24 billion each at the IPO price—fell sharply as the stock dropped, their control didn’t.

That concentration of power cuts both ways.

On the upside, it’s speed. Founder control lets Venture Global make big calls without proxy fights, shareholder revolts, or the kind of internal politics that can slow down capital-intensive businesses. If Sabel and Pender want to push forward on a project, they can. If they want to take heat in the short term for a long-term bet, they can.

On the downside, it’s accountability. When control is this concentrated, outside shareholders have limited leverage if they disagree with strategy, culture, or risk tolerance. Critics point to the customer arbitrations as an example of what can happen when a company is optimized for aggressive execution: decisions that may maximize near-term economics can also create long-term damage—especially in an industry built on decades-long relationships.

Venture Global has a board with independent directors, as a public company is expected to. But with supervoting shares in place, the board’s role is inherently constrained. It can advise. It can challenge. But it can’t ultimately overrule the people who hold the votes.

For investors, the question isn’t whether this structure is “good” or “bad.” It’s whether you’re comfortable underwriting it. The founders still have enormous economic exposure—when the stock rises, they win; when it falls, they lose—so there is real alignment on value creation. But there’s also an obvious trade: public shareholders are buying into a company where their ability to force change is limited by design.

That governance model helped Venture Global move fast and stay coherent while it tried to do something outsiders weren’t supposed to do. The harder test is what happens when the company stops being a disruptor and starts being an institution. Public-market investors expect responsiveness, transparency, and a board that can act as a true counterweight. Founder-led companies often see those expectations as friction.

Whether Venture Global can keep the benefits of founder control while earning the credibility of a mature public company is one of the biggest unanswered questions in the story—and one the market will keep pricing in until it gets clarity.

X. Playbook: Lessons in Disruption

Venture Global’s arc—from a rented Chevy making cold calls in Texas to ringing the NYSE bell—reads like a case study in how outsiders break into fortress industries. It’s also a reminder that disruption doesn’t come free. The same choices that create advantage can create enemies, lawsuits, and reputational debt.

The playbook is surprisingly portable.

The Outsider Advantage: Sabel and Pender’s lack of LNG experience wasn’t just something they had to “get past.” It was the point. The incumbents had internalized a set of rules about how LNG plants had to be designed, financed, and built. The founders treated those rules like hypotheses. When they asked “why,” the answers often boiled down to tradition. In capital-intensive industries, that’s often where the biggest openings hide: not in new demand, but in old assumptions nobody feels allowed to challenge.

Modular Thinking: Venture Global’s core insight was deceptively simple: take a project the world treats as monolithic, and break it into repeatable parts. LNG liquefaction is one of the most technically demanding processes in modern industry. Yet they pushed it toward something closer to manufacturing—factory-built modules, then assembled on-site. The broader lesson isn’t about LNG. It’s about design: when a problem looks too big to start, the first win is often figuring out where it can be made smaller.

Speed as Strategy: In commodity markets, timing isn’t a detail—it is the advantage. Faster build timelines meant Venture Global reached first production earlier, started generating cash sooner, and had capacity online in a market that suddenly became desperate for supply. That urgency became a cultural feature, not a one-off tactic. It helped them execute. It also helped create the customer blowback, because speed and optimization can collide with the slower, relationship-driven norms of long-term contracting. Still, the strategic point stands: in a market where everyone sells roughly the same molecule, being early can be the difference between a good project and a generational company.

Capital Access: Venture Global’s story is also a story about matching the right capital to the right stage. Early on, they needed belief—risk capital and partners willing to fund an unproven approach. Once they had long-term customer contracts, they could unlock project finance. Once they had operating assets, they could plausibly sell an equity story to public investors. Each step came with different expectations and constraints, and the company kept moving to the next rung of the ladder.

Regulatory Navigation: Big infrastructure doesn’t get built without permission, and permission doesn’t move at startup speed. Venture Global’s ability to navigate FERC, the Department of Energy, and state and local authorities wasn’t glamorous, but it was decisive. This is where Pender’s Washington background mattered: understanding the process, sequencing decisions, and avoiding mistakes that can cost years. In regulated markets, “knowing how it works” is as much a competitive advantage as technology.

Customer Lock-in: Long-term LNG contracts are meant to be the stabilizer in an otherwise volatile business. Take-or-pay agreements with creditworthy buyers create the predictability lenders need and the cash-flow visibility developers want. That structure is part of Venture Global’s moat. But the arbitrations show the other side of lock-in: contracts can keep customers tied to you, but they can’t make them trust you. In markets built on decades-long partnerships, the relationship is an asset too—and it’s easier to damage than it is to rebuild.

Risk Management: Venture Global’s entire model is, in a sense, a risk-management argument: modular construction to reduce schedule and execution risk, multiple customers to avoid concentration, and a mix of long-term contracts and spot exposure to balance price opportunity against stability. The disputes around commissioning cargoes suggest one risk may have been discounted too heavily: customer relationship risk. When you optimize hard in the short term, you can end up paying for it in the one place you can’t quickly refinance—your reputation.

Put together, that playbook—outsider thinking, modular construction, speed, capital sophistication, regulatory competence, and long-term contracting—built one of the most valuable new energy companies of the past generation.

The open question is whether the company can keep what made it dangerous—its pace and aggressiveness—without letting those same traits keep undermining what it needs next: durable trust, repeat customers, and the freedom to keep building.

XI. Analysis & Investment Case

The Bull Case

For believers, Venture Global is a rare kind of energy company: one that sits at the intersection of a long-running demand tailwind and a real, differentiated way of building supply.

The demand story isn’t theoretical. You can see it in the LNG import terminals going up across Asia and Europe, in government policies aimed at replacing coal with gas, and in major forecasts—like Shell’s—calling for roughly 50% LNG demand growth through 2040. If that world shows up, the winners won’t just be the companies with gas molecules to sell. They’ll be the companies that can actually build export capacity fast enough to meet it. Venture Global has shown it can.

The modular approach that got dismissed as too clever has now been demonstrated in the real world. Calcasieu Pass proved it could produce. Plaquemines proved it could be repeated. If modular construction really does keep delivering faster timelines, tighter execution, and more flexible operations, that’s not just an engineering choice—it’s a structural advantage. And like most structural advantages in infrastructure, it takes years to develop and years for competitors to copy.

Then there’s the market setup. After the IPO, the stock price effectively started trading as if the arbitration overhang was the whole story. That creates an obvious bull argument: if the disputes resolve in a way that’s “bad but manageable,” or even just become a chronic but understood cost of doing business, the gap between perception and reality could close. Public markets don’t just price fundamentals. They price uncertainty. When uncertainty falls, multiples can rise even if the business stays the same.

Finally, the policy environment has been supportive for U.S. LNG. With a declared national energy emergency and a permitting posture that favors expansion, a major historical constraint on the industry—regulatory delay—looked less binding than it had in years. For a company trying to build several Gulf Coast projects at once, that kind of political tailwind matters.

The Bear Case

For skeptics, Venture Global is a textbook example of what happens when a speed-and-optimization culture runs headlong into an industry built on decades-long trust.

The arbitrations aren’t just a legal issue. They’re a commercial signal. LNG is financed on long-term commitments, and those commitments depend on counterparties believing you’ll behave like a partner when the market gets chaotic. The customers’ allegation is essentially that Venture Global used the commissioning period to prioritize spot-market profits over contractual delivery. Even if the company ultimately prevails on the legal details, the reputational damage can linger—and reputation is a real asset in LNG. The company’s spot-market success, including the roughly $7.8 billion in spot sales in 2023 cited by Bloomberg analysis, could end up being remembered by customers as the moment Venture Global stopped looking like a new supplier and started looking like a counterparty risk.

Then there’s the simple arithmetic of capital intensity. Venture Global has laid out plans that add up to more than $100 billion in capex to complete the five-project buildout. That requires continuous access to financing on reasonable terms. After a sharp post-IPO stock decline, equity is a more expensive tool. And in project finance, anything that scares lenders—construction risk, contract uncertainty, customer pullback—can slow the machine. In businesses like this, execution mistakes don’t just hurt returns. They can interrupt the flow of capital. And interrupting the flow of capital is how megaprojects die.

Commodity exposure adds another layer of risk. LNG markets can be brutally cyclical. The conditions that made 2022 and 2023 so extraordinary—tight supply and crisis-driven demand—can reverse. New capacity from Qatar, Australia, and the U.S. can soften pricing over time. Long-term contracts dampen the swings, but they don’t eliminate them, and spot-linked economics can cut both ways.

Finally, competition doesn’t sleep. Cheniere and Sempra are expanding. Global suppliers with deep balance sheets and long customer histories keep adding trains. And if modular techniques spread, Venture Global’s early differentiation could narrow. In that world, customers may prefer “boring and dependable” over “fast and controversial.”

Porter’s Five Forces Analysis

Threat of New Entrants: Low to moderate. The barriers are still massive—permitting, engineering, and billions in capital. But if modularization becomes a repeatable template, it can lower some of the practical barriers for new developers.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers: Moderate. Feed gas is bought in a competitive market, but critical equipment and service providers—like Baker Hughes—have real leverage, and those relationships are not easily swapped out.

Bargaining Power of Buyers: Rising. As more export capacity comes online globally, customers have more options. The arbitration saga also gives buyers more reason to demand tighter terms and more protections.

Threat of Substitutes: Increasing over time. Renewables, storage, and hydrogen are the long-term substitutes. The more quickly those scale, the shorter the runway for LNG as a “bridge fuel.”

Competitive Rivalry: Intense. Many well-capitalized players are fighting for the same long-term customers, and the product itself is largely a commodity.

Hamilton Helmer's Seven Powers Analysis

Scale Economies: Limited. These are high fixed-cost assets, but the unit-cost advantage from sheer size isn’t infinite.

Network Effects: None. LNG doesn’t get more valuable because other people use the same supplier.

Counter-Positioning: Real, especially early on. Modular construction and Venture Global’s pace forced the industry to pay attention, and competitors have been pushed to respond.

Switching Costs: Moderate. Long-term contracts can lock in volumes, but the disputes show that unhappy customers will fight and will look for alternatives the moment they can.

Branding: Weak to negative right now, at least with a certain set of counterparties. In LNG, “brand” mostly means “do we trust you when the market is on fire?”

Cornered Resource: Possible. Gulf Coast sites, permits, and learned construction capability can be difficult to replicate quickly.

Process Power: Strongest candidate. Venture Global’s modular execution, if it continues to work, is a process advantage that can translate into faster schedules and better economics.

Key Performance Indicators

If you want to track Venture Global without getting lost in the noise, two things matter most:

Construction Progress vs. Plan: Are the next projects coming online on schedule and on budget? Modular construction is only a moat if it reliably produces speed and predictability.

Customer Contract Coverage: How much capacity is truly locked in under long-term contracts, and what happens to the arbitration disputes? Resolution, renewals, and new customer signings will tell you whether the company can rebuild commercial credibility—and keep financing the buildout.

XII. Epilogue & Future Scenarios

Twelve years earlier, two men with no LNG résumé were bouncing between investor meetings in a rented SUV, pitching a plan most people treated as fantasy. Now Venture Global sits at the center of U.S. LNG—operating multiple facilities, expanding along the Louisiana coast, and still valued in the tens of billions.

Which makes the ending feel strangely unsettled. Because from here, the path forks—and the next few turns will decide whether Venture Global becomes a lasting institution or a case study in how speed can outpace trust.

What happens if arbitrations go badly? The nightmare scenario isn’t just writing checks to customers. It’s the second-order effects: a public ruling that validates the accusations, a reputational scar that makes future buyers hesitate, and lenders demanding tougher terms right when Venture Global needs the market to keep funding the buildout. In a business that runs on long-term contracts, arbitration outcomes could become the defining variable.

Can they complete all five projects on time and budget? Calcasieu Pass and Plaquemines proved the modular concept can get to first production. But repeating that at full scale—across a portfolio that adds up to more than $100 billion in planned capex—puts pressure on everything: supply chains, skilled labor, contractor coordination, and the Gulf Coast’s ever-present weather risk. Even if the design is repeatable, execution at this magnitude is still a brute-force test.

Will the modular model be copied by competitors? Venture Global’s edge has never been just “modular” in theory. It’s the accumulation of know-how, the vendor ecosystem, and the ability to execute fast. But industrial advantages tend to leak. If rivals replicate the approach—or if Baker Hughes-like solutions become standard—the differentiation shrinks, and Venture Global gets pulled back toward the industry’s normal competitive battlefield: customer relationships, pricing, and reliability.

What does the next decade hold? The upside is enormous: disputes resolved, projects completed, and Venture Global operating as one of the world’s largest LNG exporters with a repeatable playbook and years of contracted cash flow. The downside is just as real: legal losses and construction strain tightening financing, forcing asset sales, or triggering some form of restructuring. For a company this big, the range of outcomes is unusually wide.

That’s the tension Venture Global throws into sharp relief. Speed versus relationships. Aggression versus durability. Disruptive innovation versus the slow grind of becoming the kind of counterparty other global giants trust for twenty years at a time.

They’ve already proven they can build world-class LNG infrastructure at remarkable speed. The harder question is whether they can build the institution around it—credibility with customers, comfort with lenders, and an operating culture that can deliver not just first gas, but dependable gas.

Sabel and Pender bet everything on an unconventional vision in an industry they didn’t grow up in. The bet has already produced extraordinary results. What decides the legacy is whether they can evolve from disruptors who build fast into operators who endure.

XIII. Recent News

Construction across Venture Global’s footprint kept moving. Plaquemines LNG reached first production in December 2024, a milestone that mattered for more than optics: it suggested Calcasieu Pass wasn’t a one-off, and that the company could replicate its modular approach at a second major site. CP2 also continued marching through the regulatory process, though its permitting timeline carried the usual uncertainty as federal energy policy continued to evolve.

The arbitration fights with BP, Shell, Repsol, Orlen, Galp Energia, and Edison remained active in international tribunals. The details of each case stayed largely confidential, but the market didn’t need to see the filings to understand the stakes. The disputes continued to hang over Venture Global’s valuation and over every future customer conversation. Management projected confidence in its legal position, while also conceding that these processes take time to resolve.

Operationally, the company’s numbers continued to underline how much earnings power sits inside a running LNG terminal. Venture Global’s Q2 2025 results showed strong momentum, with revenue and operating income growth coming in well ahead of what many expected. But the market’s attention stayed anchored on the bigger questions: can the company execute its buildout, and can it clear—or at least contain—the arbitration overhang? Near-term performance helped, but it didn’t settle the debate.

On the policy front, the backdrop was supportive. Under the current administration, the Department of Energy resumed approving export permits, and the declared national energy emergency prioritized natural gas infrastructure. Those tailwinds helped projects like Venture Global’s move with less friction. The risk, of course, is that policy is cyclical. What’s permissive under one administration can tighten under the next.

In the market, the stock’s post-IPO story remained bruising, with shares trading far below the offering price. Analyst opinion stayed split along predictable lines: bulls pointed to global LNG demand and operating execution; bears pointed to arbitration exposure and valuation. Trading activity suggested investors were still repositioning—less a settled consensus and more an ongoing argument about what Venture Global really is: a misunderstood infrastructure compounder, or a high-performing operator with a trust problem it can’t easily refinance.

XIV. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Materials - Venture Global SEC filings (S-1, 10-K, 10-Q) - Venture Global investor presentations - Annual and quarterly earnings releases

Industry Analysis - International Energy Agency LNG market reports - Shell LNG Outlook (annual publication) - Wood Mackenzie global LNG analysis - BloombergNEF LNG market research

Technical Resources - Baker Hughes LNG technology documentation - Gas Processors Suppliers Association technical standards - Society of Petroleum Engineers papers on LNG

Regulatory Documents - FERC environmental impact statements for Calcasieu Pass and Plaquemines LNG - U.S. Department of Energy export authorization orders - Louisiana Department of Natural Resources permits

News Coverage - Bloomberg reporting on Venture Global arbitration disputes - Reuters energy coverage - Houston Chronicle coverage of the LNG industry - Wall Street Journal coverage of the IPO and public markets

Academic and Research Materials - MIT Energy Initiative research on LNG - Rice University Baker Institute energy studies - Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy publications

Government Resources - U.S. Energy Information Administration LNG data - U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Fossil Energy - Federal Energy Regulatory Commission LNG project database

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music