Vertiv Holdings: The Infrastructure Behind the AI Revolution

I. Introduction & Episode Setup

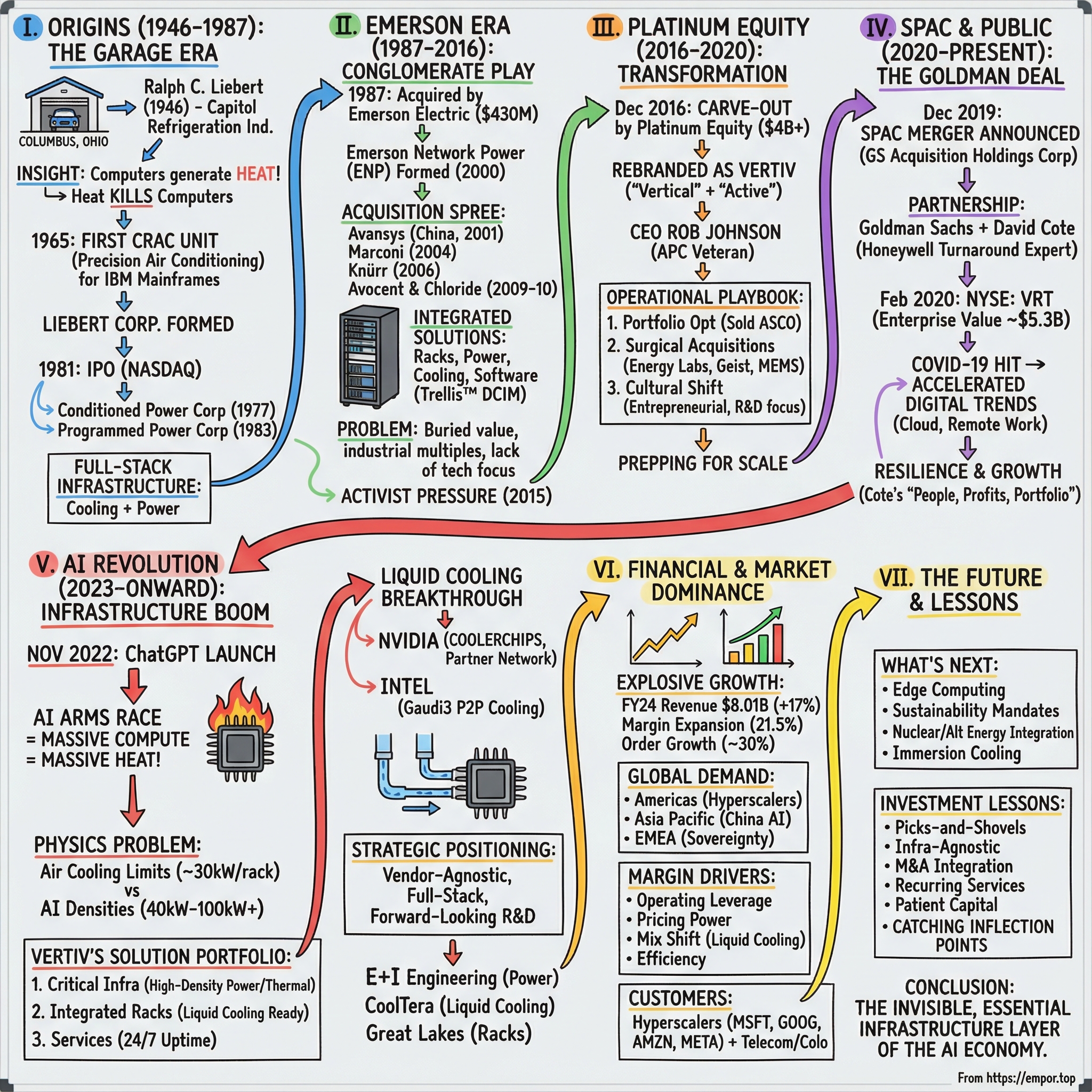

What company’s stock jumped 252% in 2023—beating every single name in the S&P 500? Not Nvidia. Not Meta. Not Tesla. It was Vertiv Holdings, a company most retail investors couldn’t pick out of a lineup, yet one that sits underneath the entire artificial intelligence boom.

While the world argued about which chipmaker would win the AI race, Vertiv was quietly becoming the picks-and-shovels play of the decade. Because every GPU training a large language model, every server rack in a hyperscale data center, every edge node doing real-time inference shares the same unavoidable reality: it produces a staggering amount of heat. And heat, if you don’t manage it, kills computers.

Vertiv is an American multinational that provides critical infrastructure and services for data centers, communication networks, and commercial and industrial environments. In normal language: they keep the digital world from overheating. They sell the power systems, the cooling, the racks, the monitoring, and the services that make modern computing reliable at scale—the unglamorous, absolutely essential backbone that turns “AI” from a demo into something that runs 24/7.

The timing here couldn’t be better. As AI workloads surge and rack power densities push from double digits toward the hundreds—and in some cases, beyond—the limiting factor stops being software and starts being physics. You can’t compute if you can’t power it, and you can’t power it if you can’t cool it. Traditional air cooling is reaching its limits. Liquid cooling is moving from “future” to “now,” and Vertiv is aiming to be the infrastructure partner behind the biggest deployments on earth.

This is the story of how a tinkerer in a Columbus, Ohio garage helped invent precision computer cooling, how that technology compounded through decades of corporate ownership, how a private equity carve-out turned a buried division into a focused operator, and why Vertiv may be one of the most important—and least understood—companies of the AI era.

II. Origins: From a Garage in Columbus to Computer Cooling Pioneer

The year was 1946. World War II had just ended, and across America, returning veterans were pouring their energy into building new lives and new companies. In Columbus, Ohio, a 28-year-old refrigeration engineer named Ralph Liebert started one of them: Capitol Refrigeration Industries.

It began the way so many great American businesses did—small, practical, and local. A garage workshop. Commercial clients. Industrial cooling jobs that paid the bills. Liebert wasn’t chasing a grand vision. He was solving the kinds of problems factories, stores, and buildings actually had.

But he had a particular kind of engineering instinct: he noticed the next constraint before everyone else ran headfirst into it.

For nearly twenty years, Capitol Refrigeration grew steadily inside Ohio’s manufacturing and commercial economy. Solid work. Solid reputation. And then, in the early 1960s, a new kind of customer started showing up in the world: the computer.

Mainframes were moving from government labs into corporate America, led by IBM. These machines were marvels—room-sized systems of vacuum tubes and, increasingly, transistors—doing work no human team could do at anything close to the same speed.

They also ran hot. Really hot.

And heat wasn’t just inconvenient. It was existential. Early computers didn’t tolerate temperature swings. Humidity could be just as deadly: too high and you risked condensation and shorts; too low and static electricity became a constant menace. The “air conditioning” that kept office workers comfortable wasn’t designed for any of this. Comfort cooling cycled on and off. It mostly cared about temperature. It treated humidity as a nice-to-have.

Computer rooms needed something else entirely: a system that could hold temperature and humidity steady, all day, every day, without drifting, without cycling, without surprises.

Liebert saw the gap. And he went back to the garage.

What he built became the prototype for the Computer Room Air Conditioning unit—CRAC. This wasn’t just a bigger air conditioner. It was precision environmental control: narrow temperature tolerances, tight humidity management, continuous operation. In other words, a machine designed for computers, not people.

By early 1965, the prototype was ready. Liebert brought it to IBM in Chicago. How a small refrigeration contractor from Ohio got a meeting with the most powerful name in computing is a story that history doesn’t fully preserve—but the outcome is clear. IBM’s engineers immediately understood what they were looking at: a real solution to a problem that was about to get much bigger.

IBM didn’t just nod politely. They helped Liebert debut the invention at the World Computer Conference in Philadelphia. For a garage inventor from Columbus, it was the equivalent of stepping onto the main stage at the most important tech event in the world. And the response was exactly what you’d expect: computer operators everywhere were fighting the same battle, and someone had finally built the right weapon.

The insight behind it was simple, almost embarrassingly so: computers generate heat, and heat kills computers. But that’s the thing—simple truths compound when the world is scaling fast. Liebert wasn’t only fixing today’s overheating mainframes. He was making a bet on a trend that would never reverse: more computing would mean more heat, and more heat would demand better cooling.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, as mainframes gave way to minicomputers and then to server rooms packed with ever more powerful machines, demand for precision cooling surged. Liebert became the trusted name in keeping computing reliable—the gold standard for controlling the invisible conditions that determined whether the machines lived or died.

Ralph Liebert passed away in 1984, but the category he created only got more important. By the time the internet era arrived, Liebert’s technology was cooling the server rooms behind the digital revolution. A business that started in a Columbus garage had helped define the infrastructure layer beneath modern computing—and laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Vertiv.

III. The Emerson Era: Building a Conglomerate Play

By the late 1990s, Liebert had grown into something real—but it was still, at its core, a specialist: a cooling company with a dominant position in a niche that was getting bigger every year. Then it ran into a different kind of force: one of America’s most disciplined industrial acquirers.

Emerson Electric, headquartered in St. Louis, had spent decades assembling an empire through deals. The formula was straightforward: buy market-leading industrial technologies, fold them into Emerson’s operating system, and use scale and process to squeeze out efficiencies. It worked across a surprisingly wide range of categories—motors, valves, automation, climate control. Now Emerson wanted to run the same play in a world that was quietly becoming mission-critical: the infrastructure behind computing.

In 2000, Emerson made the bet explicit. It created a new business unit called Network Power, pulling its critical infrastructure assets under one umbrella. The idea was simple, and in hindsight, inevitable: as the digital economy expanded, data centers wouldn’t just need cooling. They’d need integrated systems—power, thermal management, monitoring, and services—built to work together. Liebert would remain a flagship, but it would no longer be the whole story.

Then Emerson started buying the rest of the stack.

In 2001, it acquired Avansys, a power systems company, and formed Emerson Network Power India—an early signal that this wasn’t just a North America and Europe story. In 2004, it bought Marconi’s outside plant and power system business, adding telecommunications infrastructure capabilities that mattered as networks scaled alongside data centers.

In 2006 came Germany-based Knürr, which brought enclosure systems: the racks and cabinets that physically house the equipment. It sounds mundane, until you realize the data center customer doesn’t want a scavenger hunt of parts from five vendors. The more integrated the system, the more valuable the supplier.

Two more acquisitions completed the picture. In 2009, Emerson bought Avocent, adding IT management software and KVM switching—tools that brought visibility and control to the physical infrastructure. In 2010, it acquired Chloride Group for roughly $1.5 billion, one of the world’s leading UPS manufacturers, giving Emerson a major foothold in power protection.

Piece by piece, Network Power was becoming a “full stack” provider: power distribution and UPS on the way in, precision cooling on the way out, racks in the middle, monitoring software over the top, and services to install and keep everything running. For a data center operator, that’s the dream—one partner responsible for the whole critical path.

But there was a catch. Inside Emerson, Network Power was still just one division of a sprawling industrial conglomerate, competing for attention and capital alongside businesses far removed from data centers. And the market it served was changing fast—cloud computing, mobile, and the early rumblings of Big Data were accelerating the pace of infrastructure decisions.

That environment rewards focus and speed. Inside a large, diversified organization, Network Power could feel constrained—less like a dedicated data center company and more like a strategic asset waiting for permission.

Competitors, especially pure-play operators like Schneider Electric, leaned hard into the narrative that they lived and breathed data centers. Customers increasingly wanted partners who woke up every day thinking about uptime, density, and deployment speed—not organizations where critical infrastructure was one line item on an enormous org chart.

So even as Emerson had assembled an enviable portfolio, a new question started to form: was Network Power destined to be a powerful division inside Emerson—or was it going to need a life of its own to reach its full potential?

IV. The Platinum Equity Deal: Liberation and Transformation

By 2016, Emerson’s leadership had come to a conclusion: Network Power was a great business living in the wrong kind of house. It was strong, but it needed sharper focus, dedicated investment, and the freedom to move quickly—things that are hard to prioritize inside a sprawling industrial portfolio. Emerson decided to divest.

That opened the door for Platinum Equity, the Los Angeles private equity firm founded by Tom Gores in 1995. Platinum had made its name doing carve-outs—the messy, high-stakes work of separating a division from its parent and turning it into a standalone company with its own systems, culture, and priorities. Network Power would become one of the biggest carve-outs in the firm’s history.

The deal was announced in 2016 and closed in late 2017, valued at more than $4 billion. Emerson also kept a minority stake in the new company—both a vote of confidence in what had been built and a way to stay financially tied to what might come next—while Platinum took operational control and got to run its playbook.

The first visible change was the name. “Emerson Network Power” didn’t make sense anymore, so the company reintroduced itself as Vertiv. The new brand nodded to the physical reality of modern computing—servers stacked in racks, infrastructure built vertically—and to the idea of reaching a vertex, the highest point.

Platinum appointed Rob Johnson as CEO and gave him the mandate you’d expect: take a capable but conglomerate-shaped organization and make it faster, tighter, and more customer-driven. The raw ingredients were already there—excellent technology, real market leadership—but years inside a giant corporation had layered on bureaucracy and blurred priorities. Independence meant Vertiv could finally behave like what it really was: a critical infrastructure company living on the same clock speed as the data center industry.

Platinum’s approach was classic operational private equity: relentless cost discipline, clear strategic focus, and targeted investment where it mattered. Vertiv streamlined operations, cut redundancy, and put resources into sales and engineering—the teams that would actually win deployments and expand the product footprint with customers.

And Vertiv started life outside Emerson with a serious hand of cards. Liebert was still the gold standard in precision cooling. ASCO brought leadership in automatic transfer switches and power distribution. Chloride anchored UPS technology. NetSure served DC power systems in telecom infrastructure. Trellis covered data center infrastructure management software. Together, it was a broad, credible stack across power, thermal, and monitoring—exactly the set of capabilities customers wanted to buy as one integrated system.

Platinum didn’t stop at fixing the machine. It kept building.

In 2018, Vertiv made three acquisitions that extended its reach in the rack and cooling layers where customers were increasingly spending. Energy Labs added specialty cooling, including custom-engineered thermal management for high-performance applications. Geist—known for power distribution units and intelligent rack-level monitoring—strengthened Vertiv’s position inside the rack itself. MEMS added more rack power distribution capability.

The logic was consistent: close product gaps, add differentiated technology, and bring in customer relationships that Vertiv could expand with a broader offering. In a fragmented market, a well-capitalized platform with a clear strategy can compound quickly.

By the end of 2019, much of the transformation was visible. Vertiv was leaner, more focused, and better positioned for growth than it had been under Emerson. The portfolio was broader, the organization was sharper, and the company looked a lot more like a standalone leader than a division waiting its turn.

Now came the next question: how do you scale this story—and fund what’s coming—on an even bigger stage?

V. Going Public via SPAC: The Goldman Sachs Deal

Vertiv’s path back to the public markets wasn’t the classic IPO roadshow. Instead, it came through a vehicle that, at the time, still felt like a niche shortcut: a SPAC. This was before the format went fully mainstream—before the boom, the backlash, and the headlines. For Vertiv, it was simply a fast way to get a newly independent company onto a bigger stage.

The SPAC was GS Acquisition Holdings Corp, sponsored by Goldman Sachs. And the name attached to it mattered: David Cote, the former CEO of Honeywell. Cote’s reputation wasn’t built on hype. At Honeywell, he’d engineered one of the most admired industrial turnarounds in modern corporate history, taking a messy conglomerate and turning it into a disciplined operator with a relentless focus on execution. His presence signaled something important to investors: this wasn’t a “story stock.” This was an industrial company that planned to run like one.

The merger was announced in late 2019 and closed on February 10, 2020. Vertiv began trading on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker VRT. The transaction valued the company at about $5.3 billion, gave Vertiv fresh capital to keep investing, and gave Platinum Equity a clearer path to liquidity.

Cote’s involvement carried a second layer of meaning beyond credibility. The Honeywell playbook—rigorous operating cadence, continuous improvement, margin discipline, and careful capital allocation—was legendary in industrial circles. Bringing that DNA into Vertiv’s orbit told the market what kind of company this intended to be: not just a beneficiary of data center growth, but a machine built to convert that growth into durable profits.

Then the timing turned brutal. Vertiv hit the public markets only weeks before COVID-19 upended the global economy. In March 2020, markets sold off hard, and Vertiv’s stock fell with everything else. Newly public companies are especially exposed in moments like that: they don’t have long trading histories, they don’t have a wide base of familiar investors, and they haven’t had time to earn trust.

But the same crisis that rattled the markets also pulled forward the future Vertiv was positioned for. Overnight, the world leaned on digital infrastructure for work, school, healthcare, entertainment, and shopping. Demand that might have unfolded gradually arrived all at once, and data center buildouts accelerated to keep up. The digital economy didn’t pause—it surged.

Vertiv had to manage the operational chaos—supply chain stress, manufacturing constraints, and workforce disruption—while staying close to customers whose projects were suddenly even more urgent. Its global footprint helped. With operations across North America, Europe, and Asia, Vertiv had more flexibility than smaller, more regional competitors.

From there, the job was straightforward, if not easy: earn public-market confidence the old-fashioned way. Execute. Communicate targets clearly. Hit them. Over time, consistency did what volatility couldn’t: it built credibility. Quarter by quarter, results came in, margins improved, and customer demand showed up in the order book as operators locked in capacity with vendors they trusted.

SPACs would soon get a reputation for bringing questionable companies public. Vertiv was the opposite case—the structure was just the route. What showed up on the other side was a real industrial business with real tailwinds, stepping into a decade where the limiting factor in computing wasn’t code. It was power, heat, and the infrastructure needed to handle both.

VI. The Modern Portfolio: Riding the AI Wave

Walk through a modern hyperscale data center and you’ll run into Vertiv everywhere—usually without noticing. That’s the point. Their products are designed to disappear into the background, quietly doing the uncelebrated work: keeping power clean, keeping temperatures stable, and keeping systems online while the servers and chips get all the glory. But without this layer, the whole show stops.

Today, Vertiv’s portfolio spans three big buckets—each one a different piece of the “keep it running” puzzle.

Critical infrastructure and solutions is the core. On the power side, Vertiv sells both AC and DC power management—everything from uninterruptible power supplies that ride through fluctuations to power distribution that gets electricity where it needs to go. On the thermal side, it’s precision cooling: systems built to hold the environment inside a data center within tight tolerances. That includes the legacy world of traditional computer room air conditioning, and increasingly, the newer world of liquid cooling built for AI-class heat loads.

Integrated rack solutions are about packaging. Instead of customers buying a rack here, power gear there, cooling somewhere else, and then spending months stitching it all together, Vertiv can deliver pre-configured racks with power distribution, thermal management, and monitoring already integrated. It speeds deployment, reduces complexity, and makes Vertiv harder to replace once a customer standardizes on the approach.

Services and spares are the glue—and the recurring revenue engine. Data center operators don’t just buy infrastructure; they buy confidence. With more than 300 service centers and over 4,000 field engineers globally, Vertiv provides preventative maintenance, acceptance testing, engineering consulting, and emergency support wherever customers operate. When uptime is the product, having the people and parts ready matters as much as the equipment itself.

All of that would matter even in a “normal” computing cycle. But AI has forced a step-change, especially in cooling—and that’s why the liquid cooling revolution is one of the most important transitions in Vertiv’s modern story.

Air cooling was plenty for traditional server rooms. A typical rack might draw 10 to 20 kilowatts, and moving enough air across the equipment could pull the heat out efficiently. AI racks are a different species. A rack loaded with Nvidia’s latest GPUs can draw around 100 kilowatts or more, and the densest clusters push into the hundreds. At that point, air starts to lose the fight. The physics are brutal: air just can’t carry heat away as effectively as liquid can. As densities march toward three- and four-digit kilowatts per rack, liquid cooling shifts from “premium option” to “required.”

Vertiv saw that inflection coming and pushed hard into advanced cooling. It secured a $5 million grant from ARPA-E’s COOLERCHIPS program, highlighting its work in next-generation cooling technology. That, in turn, led to Vertiv being selected by Nvidia as a cooling partner for next-generation AI systems.

Intel became another important proof point. Vertiv collaborated with Intel to provide pumped two-phase liquid cooling infrastructure for the Gaudi3 AI accelerator. Two-phase cooling is a step beyond standard liquid loops: the coolant changes phase at the chip surface, absorbing far more heat, then condenses back to liquid in a heat exchanger. It’s a more advanced approach for a world where heat density is becoming the limiting factor.

Vertiv also joined the Nvidia Partner Network as a Solution Advisor and Consultant partner, reinforcing its role in the broader AI infrastructure ecosystem. Internally, the ambition is straightforward: stay aligned with—and ahead of—Nvidia’s GPU roadmap, so the infrastructure is ready when the next generation of silicon lands, not months later.

M&A has been a big accelerant here. In December 2023, Vertiv acquired CoolTera Ltd, bringing additional liquid cooling technology and expertise into the company. CoolTera added capabilities in direct-to-chip and immersion cooling, complementing Vertiv’s existing offerings as customers experiment with multiple approaches to handle AI heat loads.

Cooling isn’t the only constraint, though. Power delivery and deployment speed matter just as much, which is why Vertiv’s 2021 acquisition of E+I Engineering for $1.8 billion was so significant. E+I, based in Ireland, specialized in modular power solutions—prefabricated electrical infrastructure designed to be deployed quickly. As AI-driven demand compressed data center timelines, that “build it fast and scale it” capability became increasingly valuable.

And Vertiv kept rounding out the physical layer. In July 2025, the company announced a $200 million agreement to acquire Great Lakes Data Racks & Cabinets, expanding its integrated rack solutions portfolio and reinforcing the strategy of selling more of the stack as a unified system.

Put it all together and you can see the modern Vertiv clearly: not just a cooling company, not just a power company, but a full-spectrum infrastructure provider positioned right at the collision point of AI demand and physical reality.

VII. Financial Performance & Market Position

By the mid-2020s, Vertiv wasn’t just telling a good AI-adjacent story. The financials started backing it up in a way industrial companies rarely get to enjoy.

In the fourth quarter of 2024, net sales climbed to $2,346 million—up 26% from the same quarter a year earlier. For a company that builds physical infrastructure, that’s not a rounding error. It’s a signal that data center demand wasn’t merely healthy—it was accelerating.

Even more revealing was what happened before the revenue showed up: orders. For the trailing twelve months ending December 2024, organic orders were up about 30% versus the prior year. Orders are the clearest “forward-looking” indicator in this business. Customers don’t place them unless they’re committing to buildouts, and they don’t commit to buildouts unless they believe demand is real. A sharply rising order book is the kind of momentum you can actually build a forecast around.

For the full year 2024, Vertiv posted $8.01 billion in revenue, up 17% from fiscal 2023. That’s a very different company than the one that went public in 2020, when revenue was about $4.4 billion. In roughly four years, Vertiv went from a mid-size industrial name to an $8 billion platform—and crucially, the growth curve wasn’t flattening.

The other part of the story is quality of growth. Vertiv didn’t just sell more; it got better at turning those sales into profit. The operational discipline that came in during the Platinum Equity era carried into life as a public company. As the business scaled, fixed costs spread out, operating leverage kicked in, and profits grew faster than revenue—exactly the pattern public-market investors look for when they’re deciding whether a company deserves a premium multiple.

On the customer side, Vertiv wasn’t dependent on one hyperscaler or one telecom giant to keep the machine running. Its major customers spanned a global mix of cloud, colo, and telecom: Alibaba, America Movil, AT&T, China Mobile, Equinix, Ericsson, Siemens, Telefonica, Tencent, Verizon, and Vodafone. That breadth matters because data center spending can be lumpy. Diversification helps smooth out the inevitable pauses in any one customer’s capex cycle.

Then there’s the part most people underestimate until something breaks: service. Vertiv operated more than 300 service centers with over 4,000 service field engineers globally. In mission-critical infrastructure, that footprint is a moat. A cooling failure or power event doesn’t politely wait for business hours. Data center operators buy from vendors they believe can show up fast, with the right parts and the right expertise, anywhere their facilities are.

Against competitors, Vertiv sat in a distinctive spot. Schneider Electric was the closest peer in breadth. Eaton was strong in power management. Legrand played heavily in infrastructure products. Huawei had pushed into data center equipment markets. But Vertiv’s mix—deep heritage in precision cooling, real technology across power, thermal, and monitoring, and a scaled global service organization—gave it a differentiated profile: a specialist with a full-stack offering, built around the one thing customers ultimately pay for—uptime.

If you want a simple investor’s dashboard for this kind of business, two measures did most of the work. First: organic order growth, because it’s the earliest read on whether demand is strengthening or rolling over. Second: adjusted operating margin, because revenue growth is only valuable if it comes with discipline—and Vertiv’s ability to expand margins while scaling suggested it had both execution and pricing power.

VIII. The AI Infrastructure Boom: Timing, Technology & TAM

AI doesn’t just increase demand for data centers. It changes the rules of what a data center is allowed to be. And to understand why Vertiv suddenly sits in the blast radius of the biggest capex cycle in tech, you have to start with physics.

Traditional, general-purpose computing was built around CPUs. They draw power, sure, but the heat they generate is relatively manageable for the amount of useful work they do. GPUs built for AI are different. They’re designed to run thousands of parallel operations at once—relentless matrix math and tensor workloads—so they pull far more electricity, and almost all of that energy ends up as heat.

In the early wave of AI training, Nvidia’s H100 became the workhorse, drawing roughly 700 watts per chip. The H200 pushed toward 1,000 watts. And Nvidia’s Blackwell architecture was expected to climb again.

The real kicker is what happens when you scale that up the way the AI leaders do. AI training isn’t a “single server” problem; it’s a cluster problem. Thousands of GPUs, packed densely into racks, running hot continuously. Add it up and you’re no longer talking about the power footprint of a typical enterprise data center. You’re talking about facilities that can draw power on the order of megawatts—sometimes comparable to a small city. And because electricity doesn’t disappear, it shows up on the other side of the equation as heat that must be removed, every second of every day.

That’s why rack density has become the headline metric. Traditional data centers often ran in the range of 5 to 15 kilowatts per rack. AI-optimized environments now push into 40, 60, 80 kilowatts. The most advanced deployments reach 100-plus, and lab setups have demonstrated 200-plus kilowatts per rack. At those levels, cooling stops being a facilities detail and becomes a core design constraint.

Air cooling can only take you so far. Somewhere around 30 to 40 kilowatts per rack—depending on the specifics—it runs into practical limits. Past that point, liquid cooling isn’t a premium upgrade. It’s the only viable path. Instead of trying to move enough air to carry the heat away, you circulate coolant directly to the heat sources, pulling energy out far more efficiently. And at the extreme end, immersion cooling—literally submerging the equipment in a thermally conductive fluid—offers the highest heat removal capability.

This is where the market expansion gets startling. Projections suggest the data center infrastructure management market could reach $418 billion by 2030, growing at a 9.6% compound annual rate from 2023. But if AI buildouts keep accelerating, even those numbers may end up being too cautious.

The clearest signal is hyperscaler capital allocation. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta are each spending tens of billions annually on infrastructure. Microsoft alone has indicated capital expenditures exceeding $80 billion for AI infrastructure in the coming years. Strip away the press releases and that’s what it is: committed demand for power, cooling, and the systems around them—the exact layers Vertiv sells.

As the stakes rise, buying behavior changes too. Hyperscalers increasingly sign multi-year agreements with suppliers to lock in capacity. For Vertiv, that structure matters. It creates visibility, supports better capacity planning, and turns what used to feel like episodic project work into something closer to an industrial production schedule: the customer commits to volumes, Vertiv commits to delivery.

In that environment, competitive advantage comes down to three things: speed, scale, and expertise. Speed, because customers need solutions in months, not years. Scale, because these deployments are massive and require real manufacturing and execution capacity. Expertise, because the technology is evolving quickly, and the vendor that can’t keep up gets designed out.

That’s also why Vertiv’s stated goal—staying one GPU generation ahead of Nvidia—actually makes strategic sense. When Nvidia announces a new architecture with higher power and thermal requirements, the first question from customers isn’t philosophical. It’s practical: who can support it? By developing cooling solutions alongside the GPU roadmap, Vertiv works to make itself the default answer before the procurement cycle even starts.

IX. Playbook: Lessons in Infrastructure Investing

Vertiv’s story isn’t just a company history. It’s a case study in what tends to work when you invest in infrastructure businesses that sit underneath fast-moving technology markets.

First, the picks-and-shovels dynamic is real, and it repeats. In the Gold Rush, the most dependable money wasn’t made by the miners trying to strike it rich—it was made by the people selling shovels, denim, and supplies to everyone chasing gold. Tech waves work the same way. The headline winners can change fast. The infrastructure that every winner needs tends to compound quietly in the background.

That’s where Vertiv fits. It’s infrastructure-agnostic by design. Its cooling systems don’t care whether the heat comes from Intel, AMD, Nvidia, or custom silicon. Its power gear doesn’t care what workload is running—AI training, cloud storage, video streaming, telecom. Electricity goes in, heat comes out, and someone has to manage both. This is why Vertiv can benefit from AI infrastructure investment even if the chip leaderboard reshuffles over time.

Second, M&A matters in fragmented markets—and data center infrastructure is deeply fragmented. There are dozens of specialist vendors with one great product, one great customer set, or one piece of hard-won engineering talent. A company that has capital and can actually integrate acquisitions can stitch those pieces into a broader, more valuable platform. Vertiv has used this playbook again and again across its different ownership eras: identify a gap, buy capability, fold it into the portfolio, and sell a more complete system.

Third, services create durability. Product revenue moves with capex cycles; services help smooth the ride. But the bigger benefit isn’t just predictability—it’s proximity. When Vertiv’s field engineers are on-site maintaining equipment, they learn how the facility really runs. They build trust with the operators. And they often see expansions coming before they show up in a public order book. That relationship becomes both a wedge for cross-selling and a shield against competitors.

Fourth, capital intensity is a moat. The combination Vertiv has built—manufacturing scale, a global service footprint, and deep technical expertise in power and thermal management—can’t be copied quickly. A new entrant can’t simply “decide” to compete. Replicating those capabilities would take years of execution and enormous investment, long before the first meaningful dollar of market share is won.

Fifth, timing isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s the game. The best infrastructure companies invest ahead of the wave, when it still looks early and uncertain, because that’s when you can build product, capacity, and credibility before the scramble begins. Vertiv’s push into liquid cooling started before AI made it unavoidable. When the transition sped up, it wasn’t trying to catch up—it was already in the conversation.

Finally, switching costs in mission-critical infrastructure are real and expensive. Data center operators don’t casually rip out power systems or cooling equipment. These systems are embedded in how the facility is designed, how the staff is trained, and how reliability is managed. Changing suppliers means retraining teams, renegotiating service relationships, integrating new monitoring tools, and—most importantly—accepting transition risk. When uptime is the product, that risk is a powerful deterrent. And it’s a big reason why incumbents with proven performance, like Vertiv, can sustain customer stickiness over time.

X. Bear vs. Bull Case & Valuation

If you’re going to analyze Vertiv honestly, you can’t just ride the momentum. You have to hold two ideas in your head at once: this company sits in the middle of a once-in-a-generation infrastructure buildout, and the stock already knows it.

Start with the bull case.

The first pillar is that the AI infrastructure buildout still looks like it’s in the early innings. Yes, the spending headlines are enormous. But the actual work—building the power, cooling, and physical capacity to train bigger models, run inference at scale, and push AI into every industry—is still underway. And Vertiv isn’t selling an optional add-on. It sits on the critical path of making those deployments real.

Second, liquid cooling isn’t just incremental growth. It creates a replacement cycle. Even if the world stopped building new data centers tomorrow, the installed base would still be under pressure as compute density climbs. More AI-class hardware means more heat, and at some point air cooling simply can’t keep up. That forces retrofits and redesigns—demand that shows up not because operators want to upgrade, but because physics makes them.

Third, partnerships and early positioning matter in a transition like this. Vertiv’s relationships with Nvidia and Intel, alongside the work supported by ARPA-E’s COOLERCHIPS grant, suggest it didn’t stumble into liquid cooling late. It has been in the lab, in the field, and in the roadmap discussions. In markets where the requirements change every GPU generation, being early isn’t a marketing advantage—it’s how you avoid being designed out.

Fourth, there’s operating leverage. Vertiv has already shown that as revenue scales, profits can scale faster. If it keeps executing—tight operations, disciplined pricing, better mix—margin expansion becomes a real engine, not just a spreadsheet assumption.

Now the bear case—because there are real ways this can go wrong.

The most obvious one is valuation. When a stock rerates hard, the multiple becomes its own source of risk. If growth comes in even a little below what the market is now pricing, multiple contraction can do more damage than the business can offset with incremental earnings. Great companies can still be bad investments if you pay too much at the wrong time.

Then there’s cyclicality. Vertiv ultimately sells into data center capex. Hyperscalers can speed up, slow down, or pause based on macro conditions, internal digestion cycles, competitive pressure, or shifts in how they deploy workloads. In this business, a capex slowdown tends to show up quickly in orders—and orders are the leading edge of everything else.

Competition is another real threat. Schneider Electric brings global scale and a broad portfolio and competes aggressively. Lower-priced alternatives, particularly from Asian manufacturers, can pressure pricing in parts of the market. And the biggest customers—companies with enormous data center footprints—always have the option to bring more in-house if they believe it’s strategic or if vendor capacity gets tight.

Finally, there’s technology risk. Cooling is evolving quickly, and there isn’t a single guaranteed “winner” across every density and deployment type. Direct-to-chip, immersion, and other approaches each have tradeoffs. If the industry standardizes around a direction Vertiv underestimates—or if it overinvests behind the wrong architecture—product leadership can erode, and with it the premium positioning.

You can also pressure-test this with frameworks, if that’s your style. Porter’s Five Forces paints a business with moderate supplier power, moderate buyer power, high barriers to entry, a moderate threat of substitutes, and intense rivalry. In other words: not an easy arena, but one where incumbency and execution matter a lot.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers lens, Vertiv’s advantage looks less like a classic software moat and more like industrial compounding: scale economies as volumes grow, meaningful switching costs once customers standardize a facility design and service relationship, and cornered resources in brand heritage and accumulated expertise—especially in precision cooling. Network effects are limited, but process power shows up in the operating discipline the company has built over time.

Ultimately, the valuation question comes down to belief. The market price implies AI infrastructure spending will stay elevated and that Vertiv will hold or expand its position as the “critical path” supplier. Those aren’t crazy assumptions—but they do require years of strong execution, through cycles, while technology keeps moving.

XI. The Future: What's Next for Vertiv

If the last decade of data center growth was about building a few enormous “cloud factories,” the next decade looks like it will also be about spreading compute out. Edge computing and distributed infrastructure are the next frontier: AI models won’t live only in centralized hyperscale campuses, but increasingly at cell towers, retail locations, factory floors, and inside industrial environments where decisions need to happen in real time. And once compute moves, the unglamorous necessities move with it—power, cooling, monitoring, and service. The edge brings constraints that hyperscalers don’t always face: tight footprints, harsh conditions, and sites that are difficult to staff. That pushes demand toward purpose-built, highly reliable systems that can run with minimal hands-on attention.

At the same time, sustainability and energy efficiency are becoming decision-makers, not side quests. Data centers draw enormous amounts of electricity, and operators face rising pressure—from regulators, customers, and investors—to prove they can grow without wasting power. In that world, thermal management isn’t just about preventing failure. It’s about efficiency. Solutions that reduce energy consumption and improve how effectively heat is removed can become a real competitive advantage, because they lower operating cost and make permitting and expansion easier.

Power supply itself may also change. Nuclear power and alternative energy integration are emerging opportunities as operators look for reliable, carbon-free sources of electricity. Small modular reactors and other alternatives are increasingly part of the conversation, not science fiction. If new power sources come online, the next bottleneck becomes the infrastructure that connects them to data center loads safely and predictably—another potential category for vendors that understand mission-critical power at scale.

Geographically, there’s still plenty of map left to cover. Vertiv already has a global presence, but growth opportunities remain substantial—especially across parts of Asia and in emerging economies where cloud computing and AI adoption are still earlier in their buildout curves. As those markets scale, they won’t just need chips and servers. They’ll need the physical systems that keep them running.

Then there’s the biggest constant in this entire story: the technology won’t sit still. The next generation of cooling will keep evolving—whether through refinements to liquid cooling, new approaches, or techniques that haven’t yet become mainstream. The lesson of every infrastructure transition is simple: companies that stop investing in R&D don’t hold their position for long. In a rapidly changing market, leadership has to be earned continuously.

That’s why M&A likely stays on the table. Data center infrastructure remains fragmented, with specialists scattered across niches like monitoring software, advanced cooling, and regional service. Those companies can be useful building blocks—ways to fill product gaps, add talent, and expand presence where customers are growing fastest.

Finally, consolidation feels like the natural endgame as the category matures. Smaller players may struggle to fund competitive investment, while larger ones chase the benefits of scale. Vertiv’s position—large enough to be a platform, but not so large that it owns the market—keeps both options open. It can keep acquiring to widen the stack, and over a long enough horizon it could also become an attractive target for an even larger industrial company that wants meaningful exposure to data center infrastructure.

XII. Links & Resources

Company filings and official sources - Vertiv Holdings Co annual reports (Form 10-K) and quarterly reports (Form 10-Q) via SEC EDGAR - Vertiv Holdings Co Investor Relations site for earnings decks, webcasts, and transcripts - Proxy statements for governance and executive compensation details

Industry research - Grand View Research coverage of the data center infrastructure management market through 2030 - Uptime Institute annual reports on data center reliability, efficiency, and operating best practices - ARPA-E COOLERCHIPS program materials on next-generation cooling R&D

Recommended reading - “The Datacenter as a Computer” (Barroso, Clidaras, and Hölzle) for how hyperscalers think about data centers as systems - Trade outlets like Data Center Dynamics and Data Center Knowledge for the week-to-week pulse of the industry

Management commentary - Quarterly earnings call transcripts to track how Vertiv describes demand, supply constraints, pricing, and competitive dynamics - Conference talks and investor presentations where management lays out the product roadmap and long-term strategy

XIII. Recent News & Developments

Vertiv’s fourth quarter 2024 results showed that the demand story wasn’t cooling off. Net sales rose to $2,346 million, and organic orders held at roughly 30% year-over-year growth. Management pointed to broad-based strength—across customer types and across regions—which is exactly what you want to see in a business that can otherwise get whipsawed by a single hyperscaler’s budgeting cycle.

On the technology front, the Nvidia relationship has kept getting more substantive, with Vertiv supplying thermal solutions for next-generation AI systems. Work supported by the ARPA-E COOLERCHIPS grant has also started to translate from R&D into commercial deployments—an important milestone, because in this market “in the lab” only matters once it becomes “in the field.”

Vertiv has also kept pushing its portfolio outward. In July 2025, it announced an agreement to acquire Great Lakes Data Racks & Cabinets for $200 million, a move that reinforces the integrated-rack strategy: sell more of the physical stack as a unified system, and make deployment easier for customers. The company said integration was progressing according to plan.

Perhaps the most telling shift has been on the customer side. Liquid cooling adoption has moved faster than many expected, with customers increasingly specifying liquid-capable infrastructure even when they aren’t fully committed to AI workloads yet. In other words, they’re designing for optionality—building data centers that can handle the next wave of heat loads whenever the workload mix catches up.

To meet that demand, Vertiv has continued investing in capacity, including manufacturing footprint additions in North America and Asia. Lead times have come down from pandemic-era extremes, but they’ve remained longer than historical norms—less a sign of dysfunction than of sustained demand in an industry that’s still sprinting to add supply.

Finally, policy has started to matter more. Regulatory attention on data center energy consumption—particularly in parts of Europe and certain U.S. states—has pushed efficiency higher on the priority list. That dynamic tends to favor vendors that can deliver measurable thermal improvements, adding a tailwind for Vertiv’s advanced cooling offerings as customers try to grow without running into energy and permitting walls.

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music