Wabtec: The Story of America's Rail Technology Giant

I. Introduction & Episode Roadmap

Picture this: February 2019. In a Pittsburgh boardroom, executives sign the kind of paperwork that would’ve made George Westinghouse do a double take. The company he started 150 years earlier to stop trains from killing people was about to take over General Electric’s storied locomotive business—the outfit whose engines had pulled American rail for generations. How does an air-brake company end up owning one of industrial America’s crown jewels?

Wabtec Corporation—its name a mash-up born from the 1999 merger of Westinghouse Air Brake Company and MotivePower Industries—is one of those rare industrial stories that stretches across the full arc of modern American business. It runs from steam-era invention to battery-electric experiments; from a young inventor’s breakthrough to a Fortune 500-scale enterprise bringing in more than $8 billion a year as of 2019. This is a story about patient operators, relentless consolidation, and a company that kept finding new ways to matter as the world changed around it.

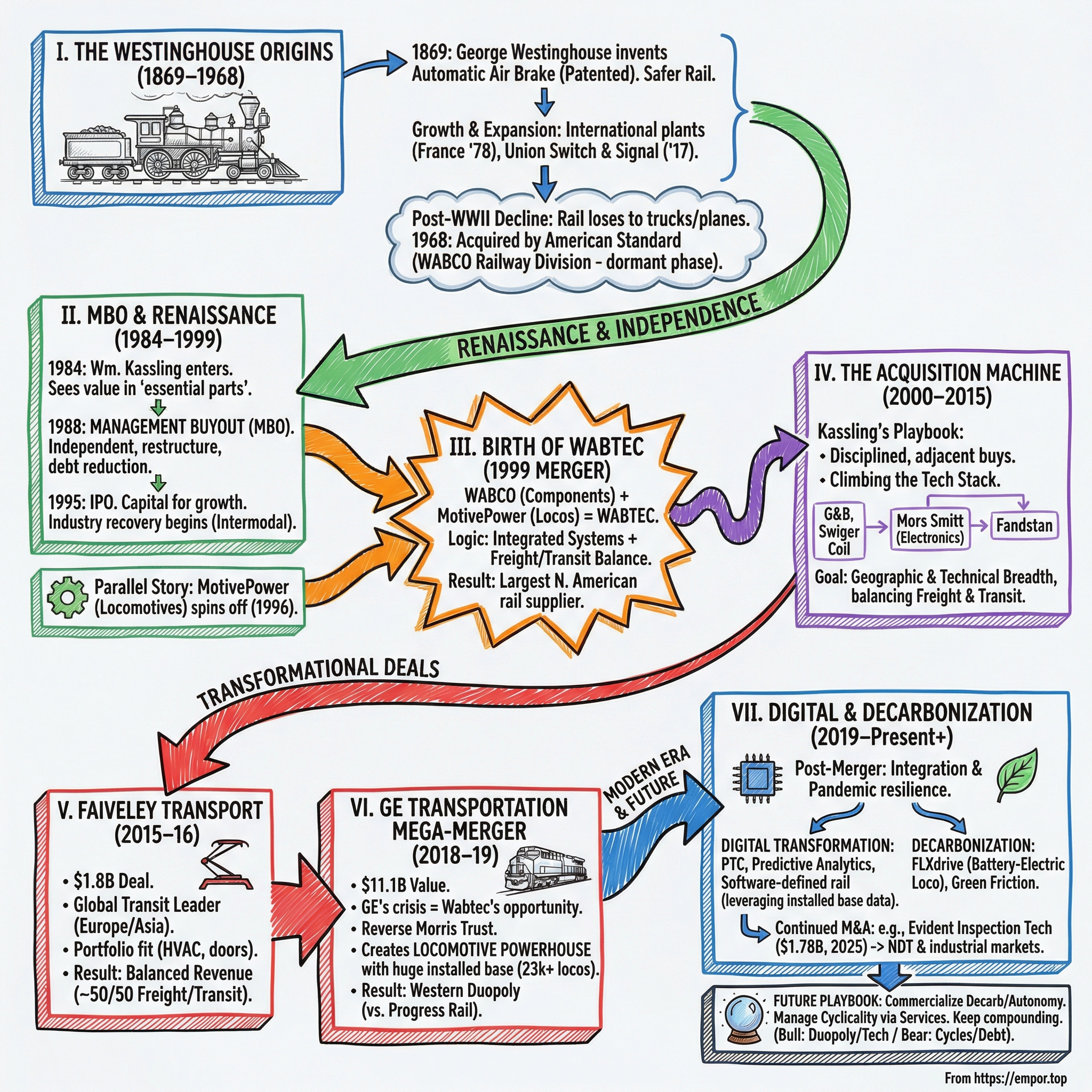

We’re going to tell it in three big acts. First: the origin story, when George Westinghouse Jr. creates the automatic air brake in 1869 and makes modern railroading dramatically safer. Second: the long middle—growth into an industrial powerhouse, followed by industry decline, and then a surprising rebirth via a scrappy management buyout. Third: the acquisition era, when Wabtec turns M&A into a core competency and, deal by deal, builds the platform that ultimately enables the GE Transportation combination.

Along the way, the themes extend far beyond rail: how legacy industries respond to disruption, why cyclical businesses can reward the teams built for endurance, and what it looks like when a century-and-a-half-old company bets on the future—digital systems, analytics, and decarbonization—to stay essential. Rail may feel nineteenth century. The game behind it is anything but.

II. The Westinghouse Origins: Air Brakes Change Everything (1869–1968)

A Young Inventor's Dangerous Obsession

In the late 1860s, American railroads had a problem that was equal parts operational headache and human tragedy: trains couldn’t stop safely.

To slow a freight train, brakemen, often little more than boys, climbed onto the tops of moving cars and, at the engineer’s whistle, cranked brake wheels by hand. In rain, snow, and darkness, they ran from car to car over slick planks and gaps. One wrong step meant a fall between cars, and then the wheels. Even when everything went “right,” the system was slow and uneven. A long train might have some cars braking hard, others not at all, and the whole thing took so long to stop that collisions were a grim fact of life.

George Westinghouse Jr. was born in 1846 into a well-off New York manufacturing family, the kind of environment that produces tinkerers with confidence. By his early twenties he already had patents to his name—one for a railroad frog, another for a device to re-rail derailed cars. But it wasn’t a workshop problem that grabbed him next. It was what he saw on the rails: a crash, two trains plowing into each other because they simply couldn’t stop fast enough.

It turned into an obsession with a deceptively simple question: how do you make every car on a train brake at the same time?

The spark came from far outside railroading. Westinghouse read about tunnel projects in Europe where engineers used compressed air to run drills, pushing power through long pneumatic hoses. If air pressure could travel that distance and still do work, why couldn’t it carry braking force down the length of a train? Instead of relying on scattered human muscle, one system could command every wheel, all at once.

The Automatic Air Brake Patent

On April 13, 1869, Westinghouse received the patent for the automatic air brake. It wasn’t just that he used compressed air. It was how he used it.

His design was fail-safe. Air pressure held the system in a “ready” state; if a hose ruptured or a car broke loose, the loss of pressure triggered the brakes automatically. In the very scenarios that caused the worst accidents—separations, ruptures, sudden failures—the train would stop itself.

The early tests made the point better than any sales pitch. Westinghouse persuaded the Panhandle Railroad to let him demonstrate the system on a passenger train. On one run, a horse-drawn wagon got stuck on the tracks ahead. The engineer applied the air brake and stopped in time. With manual braking, it would’ve been a catastrophe.

Railroads noticed. Quickly.

Within a year, Westinghouse incorporated the Westinghouse Air Brake Company and started manufacturing. Adoption climbed fast. By 1880, a majority of American locomotives and a large share of passenger cars were equipped with Westinghouse air brakes. By 1890, when federal law required air brakes on trains, Westinghouse was already close to standard. The company didn’t need a legal monopoly; technology, timing, and a huge safety advantage did the job.

Building the Empire

Westinghouse didn’t intend to be a one-invention wonder. Air brakes produced real profits, and he reinvested them aggressively—into capacity, into talent, and into reach.

In 1878, the company opened its first overseas manufacturing plant in France, its first step toward becoming an international industrial player. By the 1880s, Westinghouse Air Brake was selling across Europe and beyond, following railroads as they spread and modernized around the world.

It also expanded into the adjacent systems that made railroads function. In 1917, Westinghouse Air Brake acquired Union Switch & Signal, moving into signaling and control. Strategically, it was obvious: the same customers buying braking equipment were also buying the infrastructure that prevented trains from meeting each other on the same track. Technically, it fit too—mechanical reliability, precision manufacturing, and a deep understanding of railroad operations.

This wasn’t a one-off. It was an early example of a growth pattern that would become central to the company’s identity: widen the product portfolio, deepen the customer relationship, and do it through targeted acquisition as much as internal R&D.

George Westinghouse died in 1914, with the world on the cusp of industrial upheaval. He left behind multiple legacies, including Westinghouse Electric, founded separately, which would grow into an American industrial giant. The air brake company carried on in its own right, supplying railroads through World War I, World War II, and the peak decades of American rail.

The Long Decline

Then came the postwar shift—slow at first, and then unstoppable.

After World War II, railroads began losing the battles that mattered most. Freight moved to trucks, increasingly empowered by better roads and, eventually, the Interstate Highway System. Passenger traffic drained away to cars, buses, and then airlines. Route networks shrank, once-mighty rail names slid toward bankruptcy, and the industry that had built modern America started to look, to many investors, like yesterday’s story.

For Westinghouse Air Brake, that meant a painful reality: fewer trains, fewer cars, fewer orders. The company tried to outrun the decline the only way an engineering-driven business knows how—by innovating and expanding into new categories. Its engineers developed early electronically controlled braking systems, technology sophisticated enough to be used on the original Metroliner cars and rapid transit vehicles in major U.S. cities.

But even strong technology couldn’t fully offset the underlying trend. Traditional railroad equipment demand was shrinking, and Wall Street’s appetite for rail exposure was shrinking with it.

In 1968, American Standard acquired Westinghouse Air Brake and folded it into its Railway Products Group, renaming the division WABCO Railway. For an independent company that had once defined an industry, it was a quiet, corporate ending—at least on paper. The Westinghouse air brake legacy survived inside a conglomerate that largely treated rail as a mature, declining category: something to maintain, not something to bet on. For the next sixteen years, WABCO would operate in that in-between state, alive, capable, and waiting for the moment it could become a growth company again.

III. The Management Buyout & WABCO Renaissance (1984–1999)

Enter William Kassling

WABCO might have looked like a sleepy division inside a conglomerate, but in 1984, American Standard put it in the hands of someone who didn’t see “decline.” William E. Kassling took over the Railway Products Group and spotted the thing corporate owners often miss: even in a shrinking market, the supplier of mission-critical parts can be a great business.

Railroads still had to run. Trains still had to stop. Signals still had to work. And the companies that kept fleets safe and compliant didn’t get swapped out lightly. Kassling believed WABCO had durable customer relationships, real competitive advantages, and—because the products were essential—more pricing power than anyone wanted to admit.

He spent the next four years building the plan and assembling the right internal coalition. Then, in 1988, he and his team did the bold thing: they bought it. The management buyout pulled the Railway Products Group out of American Standard, financed with debt and backed by management’s own capital. It was the classic high-stakes setup. If the business sputtered, they’d feel it personally. If it worked, they’d finally control their own destiny.

For the next two years, the newly independent company, still operating under the WABCO name, did the hard, unglamorous work: restructuring operations and grinding down debt. By 1990, WABCO was fully independent for the first time since 1968. Kassling’s playbook was clear and disciplined—tighten costs, expand margins, and be ready when the cycle inevitably turned.

The 1995 IPO and Strategic Repositioning

In 1995, WABCO went public. The IPO brought in fresh capital to keep deleveraging and, just as importantly, to start buying. This was still viewed as a mature, cyclical rail supplier, so expectations weren’t sky-high. But public shares gave Kassling something powerful: a currency for consolidating a fragmented industry.

And the timing couldn’t have been better.

After decades of rail feeling like the loser in a trucking-and-airline world, freight traffic began to recover in the early 1990s. Trucking faced higher costs and driver constraints. Rail’s fuel-efficiency edge mattered more. And intermodal matured—containers moving smoothly between ships, trains, and trucks, making rail competitive again for freight that had migrated to highways. On long hauls, intermodal could win on economics.

The comeback surprised plenty of people. Railroads that had been written off started growing traffic, investing in infrastructure, and placing orders. WABCO felt it quickly. The order book improved. The “declining asset” inside American Standard suddenly looked like a business with momentum.

The MotivePower Parallel Story

While Kassling was rebuilding WABCO, another rail business was taking shape out west—this one centered not on components, but on the locomotive itself.

Morrison Knudsen, a diversified construction and engineering company, had accumulated locomotive manufacturing capabilities and in 1994 created a subsidiary called MK Rail Corporation to house the operation. But Morrison Knudsen was under financial pressure, and in 1996 the rail unit split away and took a new name: MotivePower Industries Corporation.

MotivePower did what WABCO didn’t. It built and rebuilt locomotives—big-ticket, high-complexity work with long production cycles. From its facility in Boise, Idaho, it produced new locomotives and performed major overhauls for railroads across North America. In the rail ecosystem, it sat further up the value chain, closer to the prime contractors and the largest equipment decisions.

By the late 1990s, both companies were doing well—and both could see their ceilings. WABCO had the components, electronics, and installed relationships, but limited ability to deliver larger integrated systems. MotivePower had locomotive expertise, but a narrower portfolio. Each was a strong mid-sized industrial player on its own. Put together, they had the makings of something far more formidable.

IV. The Birth of Wabtec: WABCO + MotivePower Merger (1999)

The Strategic Logic

By the late 1990s, WABCO and MotivePower had both earned something rare in rail: momentum. But they’d also run into the limits of being mid-sized specialists in an industry that was steadily consolidating.

So in 1999, they announced a merger to create a new company: Wabtec Corporation. The name—short for Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation—was a nod to the heritage, but it also sounded like what the company wanted to become: a modern rail technology platform, not just an old-line parts supplier. The merger was pitched as a combination of equals, even if WABCO shareholders ended up with the larger stake.

The logic was straightforward and, for once, not just banker poetry. Together, the companies could cover far more of the railroad’s spend—components, electronics, services, and, through MotivePower, entire locomotives. And railroads were increasingly motivated to buy that way. They wanted fewer vendors, tighter integration, and partners that could take on bigger chunks of the system without turning every project into a multi-supplier coordination problem. A company that could show up with both parts and platforms would be harder to displace.

There was also a quieter benefit: stability. WABCO leaned heavily into freight, tied to the ups and downs of North America’s big Class I railroads. MotivePower had more exposure to transit and commuter customers, where budgets and demand could be shaped by government funding and longer planning cycles. Put them together, and you didn’t eliminate cyclicality—but you could blunt the worst of it.

Creating a Diversified Powerhouse

When the deal closed, Wabtec stepped onto the field as the largest North American supplier of rail equipment and services, with annual revenue north of a billion dollars. It also became the world’s largest publicly traded rail equipment supply company—a detail that mattered because it gave investors a clean, scaled way to bet on rail globally.

The integration, of course, wasn’t magic. “Merger of equals” usually means double the committees and twice the arguments, and Wabtec had the standard issues: duplicated facilities, overlapping products, and two organizations that weren’t used to taking direction from each other. Pittsburgh became the corporate center, while MotivePower’s locomotive operations continued from Boise and elsewhere. Sorting out the combined footprint took years, and it came with the kind of difficult calls—consolidations, closures, organizational rewiring—that don’t make it into the celebratory press release.

But the central bet held. Customers responded to the broader offering, and the company started finding real cross-sell opportunities—locomotive buyers discovering Wabtec’s components and electronics, and component customers getting pulled into bigger system conversations. With more scale came more leverage: better purchasing power with suppliers and more credibility with the railroads that preferred not to depend on a patchwork of smaller vendors.

Most importantly, the merger gave William Kassling—now CEO of the combined company—the platform he’d been building toward. The rail supply world was still fragmented, full of specialized businesses by product niche and geography. With Wabtec’s size, public currency, and an operator’s mindset, it was suddenly positioned to do something bigger than just compete.

It could start buying the industry.

V. The Acquisition Machine: Building Through M&A (2000–2015)

Kassling's Acquisition Playbook

Once Wabtec had the platform, Kassling did what great consolidators do: he turned buying into a process, not an event.

The rules were simple. Look for businesses next door to what Wabtec already did—adjacent product lines, tuck-in technologies, or footholds in new geographies where Wabtec’s existing sales channels could suddenly sell a lot more. Don’t overpay. Avoid splashy auctions and inflated valuations, and instead focus on smaller, often overlooked companies where operational discipline and scale could create real value. And then, once the deal closed, move fast—integrate, streamline, and get the benefits showing up in the numbers quickly.

Through the 2000s, the cadence picked up. In 2010, Wabtec bought G&B Specialties and Bach-Simpson for a combined forty-four million dollars, adding specialty castings and electronic components. Later that year it acquired Swiger Coil Systems for about forty-three million dollars, bringing in electromagnetic coil expertise used in locomotives and transit vehicles. None of these deals were meant to remake the company overnight. That was the point. They were small enough to digest without drama, but each one widened the product catalog and deepened Wabtec’s role in the rail supply chain.

Building Geographic and Technical Breadth

In 2012, Wabtec stepped up in size with the acquisition of Mors Smitt Holding for about eighty-eight million dollars. Mors Smitt, based in the Netherlands, specialized in relays and electronics for rail—products that fit naturally with where the industry was headed, and that also gave Wabtec more weight in Europe. Two years later came another meaningful expansion: Fandstan Electric Group, acquired for nearly two hundred million dollars, which further strengthened Wabtec’s electronics lineup.

Zoom out and a pattern becomes obvious. Wabtec wasn’t just collecting revenue. It was steadily climbing the technology stack.

Rail was moving from mechanical to electronic—more sensors, more onboard computing, more diagnostics, more communication between locomotives, cars, and the network around them. Wabtec’s legacy mechanical strengths still mattered, but Kassling understood they wouldn’t be enough on their own. These acquisitions were a way to buy capabilities—and talent—that would position the company for the digital shift already underway.

And just as important, Wabtec kept balancing freight with transit. Freight rail could be a roller coaster. Transit agencies and commuter railroads bought on different cycles, often tied to long-term, government-funded programs. A broader mix didn’t eliminate cyclicality, but it smoothed the ride.

The Cyclical Recovery Continues

All of this played out against a healthier backdrop for rail than anyone would’ve predicted a decade earlier. Intermodal kept growing as shippers leaned into rail’s efficiency on long-haul routes. Core commodity volumes—coal, grain, chemicals—remained significant even as the overall mix evolved. Railroads themselves got more efficient, pushing down costs and improving performance as new operating approaches spread.

For Wabtec, that meant multiple engines of growth at once. Locomotive orders supported the MotivePower side of the house. Aftermarket parts and services—where the installed base creates recurring demand—became a steady, high-margin pillar. And international expansion, especially in transit, widened the map.

By 2015, Wabtec no longer looked like a former division of American Standard that had merely survived. It was a global, diversified rail technology supplier built deal by deal—disciplined, patient, and increasingly hard to ignore.

Which is exactly what set the stage for the next era: acquisitions that wouldn’t just add capabilities, but redefine the company’s center of gravity.

VI. The Faiveley Transport Acquisition: Going Global in Transit (2015–2016)

A Bold Cross-Border Play

In July 2015, Wabtec went from steady dealmaker to headline buyer. It announced plans to acquire Faiveley Transport, a French rail supplier that would instantly push Wabtec deeper into the global transit market. The price tag was about $1.8 billion including debt—easily the largest acquisition in Wabtec’s history. This wasn’t another neatly sized add-on. It was Wabtec betting it could combine two major industry players and come out stronger.

Faiveley brought its own long arc of rail heritage. Founded by the Faiveley family in 1919 to serve French railways, the company had spent decades building a footprint across Europe and Asia. It was best known for the equipment that makes modern electric transit work: pantographs (those articulated arms that reach up to the overhead wires), along with brakes, HVAC systems, and platform screen doors. It was a broad catalog, sold into complex projects, with long customer relationships—exactly the kind of business Wabtec liked.

The case for the deal came down to three clear benefits. First, geography: Faiveley operated in more than 24 countries, especially in Europe and Asia—regions where Wabtec wanted more scale. Second, portfolio fit: Faiveley’s products largely complemented Wabtec’s, creating a natural cross-sell story without turning the merger into a brutal overlap fight. Third, technology: Faiveley had real credibility as an innovator, including introducing the single-arm pantograph back in 1955 and continuing to develop systems like energy recovery.

Regulatory Complications

Big, cross-border industrial deals rarely go straight to the finish line, and this one didn’t. Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic took a hard look at where the combined company might have too much market power.

In the U.S., the Department of Justice focused on freight car brakes—one of the few areas where Wabtec and Faiveley meaningfully overlapped. The remedy was blunt: Wabtec agreed to divest Faiveley Transport North America’s entire U.S. freight car brakes business. It was a real give-up, but it removed the biggest obstacle to approval.

Europe ran its own process, examining competition across multiple transit equipment categories and geographies. Reviews stretched into 2016, and the longer timeline put a different kind of pressure on Wabtec’s team. When a deal drags, you’re tempted to tweak terms just to get it done. The discipline is not doing that—staying committed without overpaying for closure.

Integration and the Transit Platform

The acquisition finally closed on December 1, 2016, for roughly $1.7 billion. Wabtec slotted the business into its Transit Group and kept the Faiveley brand in markets where it carried real weight. The integration approach was pragmatic: preserve local expertise and customer intimacy, but plug Faiveley into Wabtec’s operating system and global resources.

Strategically, the impact was immediate. Before Faiveley, Wabtec skewed heavily toward freight—about two-thirds of revenue—while transit was closer to a third. After the deal, the mix moved much closer to even. That mattered because it dampened earnings volatility and gave Wabtec a stronger seat at a different table: the global transit investment cycle, driven by long planning horizons and the steady push of urbanization.

And just as importantly, Faiveley became a proof point. Wabtec had shown it could handle a large, complicated acquisition—regulatory hurdles, divestitures, integration—without losing control of the finances. Debt rose, but stayed manageable. Synergies arrived roughly as promised. That credibility would become invaluable, because an even bigger swing was coming—one that would change Wabtec’s trajectory entirely.

VII. The GE Transportation Mega-Merger: Transformational Deal (2018–2019)

GE's Existential Crisis Creates Opportunity

By 2018, General Electric—once the most valuable company in America—was in trouble. Years of sprawl, missteps, and financial strain had caught up. New CEO John Flannery, and then his successor Larry Culp, weren’t talking about expansion anymore. They were talking about triage: simplify the company, sell assets, pay down obligations, and restore credibility.

That put GE Transportation on the table.

Headquartered in Erie, Pennsylvania, GE Transportation built the iconic blue-and-white locomotives that hauled freight across North America. It had been part of GE for more than a century, with deep engineering roots and a huge installed base. But in GE’s new world, “great business” wasn’t the same as “core business.” Transportation didn’t fit the portfolio GE was trying to become. So even a category leader could be labeled non-core.

For Wabtec, this was the opening Kassling’s whole strategy had been building toward. Buying GE Transportation wouldn’t just add product lines. It would change what Wabtec was. Overnight, Wabtec would go from a diversified rail equipment supplier to a scaled locomotive platform—able to design, build, equip, and service locomotives across their entire operating lives.

The Deal Structure

On May 21, 2018, Wabtec announced a definitive agreement to combine with GE Transportation. The deal was structured as a Reverse Morris Trust, a tax-efficient structure that let GE extract value while deferring capital gains taxes.

The headline terms were big. GE received $2.9 billion in cash at closing. GE and its shareholders ended up with roughly 49% ownership of the combined company. GE Transportation was valued at $11.1 billion—an enormous transaction relative to Wabtec’s pre-deal size, and a clear signal that this wasn’t a tuck-in. It was a transformation.

When the deal closed on February 25, 2019, the ownership math settled into a slightly unusual shape: legacy Wabtec shareholders owned about 51% on a fully diluted basis, GE shareholders held roughly 24%, and GE itself retained about a 25% economic interest.

That structure mattered beyond spreadsheets. GE still had real skin in the game, which kept incentives aligned. But Wabtec kept operational control—meaning the integration would be run by the team that had spent two decades turning acquisitions into a repeatable operating system.

Integration Challenges and Synergy Targets

Wabtec projected $250 million of annual run-rate synergies within three years. On top of that, the Reverse Morris Trust created an estimated net present value of about $1.1 billion in tax benefits—real dollars that would accrue over time.

Still, the work ahead was massive. GE Transportation brought around 27,000 employees across 50 countries into the fold. The combined company inherited an installed base of more than 23,000 locomotives worldwide—an enormous aftermarket opportunity, and an equally enormous obligation to keep fleets running. Plants, engineering organizations, supply chains, and sales teams all had to be stitched together without breaking what customers depended on.

The near-term backdrop helped. GE Transportation was coming off a down period but was positioned for a rebound, with estimated adjusted EBITDA expected to rise from about $750 million in 2018 to between $900 million and $1 billion in 2019. Freight markets were improving, new locomotive demand was stabilizing, and the service business kept throwing off recurring revenue from that installed base.

A New Industry Structure

The combination didn’t just reshape Wabtec. It reshaped the industry.

Post-deal, Wabtec became one of only two Western companies capable of building large diesel-electric freight locomotives, alongside Caterpillar’s Progress Rail. In China, CRRC—formed by the merger of state-owned manufacturers—dominated its home market, but geopolitical barriers limited its reach in North America and much of Europe.

For customers, the implications were clear. There were fewer big choices, but the remaining suppliers could do more. A Class I railroad could buy locomotives from the new Wabtec and also source brakes, signals, and digital systems from the same company—reducing vendor complexity and making integrated solutions more practical. And in the aftermarket, scale compounded: with that combined installed base, Wabtec became a default partner for maintenance, upgrades, and modernization over multi-decade life cycles.

At a moment when mega-mergers were often treated as value-destroying vanity projects, this one landed differently. Wabtec wasn’t trying to become something unfamiliar. It was extending a strategy it already knew how to execute—only now, the prize was one of the most storied locomotive franchises in American industry.

VIII. Modern Era: Digital Solutions & Decarbonization (2019–Present)

Post-Merger Evolution

The GE Transportation deal closed in early 2019. Almost immediately, the world made sure Wabtec didn’t get a gentle integration.

Freight softened late that year. Then came the pandemic—whiplashing demand, snarling supply chains, and a global industrial system that suddenly couldn’t count on anything arriving on time. Through it, Wabtec did what it had trained itself to do for two decades: run the playbook. Consolidate facilities where it made sense. Use the new scale to squeeze purchasing costs. Simplify overlapping product lines. And keep the trains running for customers who couldn’t afford disruption.

Out of that work came a cleaner operating model: two segments, Freight and Transit. Freight—roughly two-thirds of revenue—held the big GE inheritance: locomotive manufacturing, components, and an expanding set of digital offerings for freight railroads. Transit—about a third—served passenger rail and metro systems globally with equipment and long-lived service relationships.

Digital Transformation

If the GE combination changed Wabtec’s scale, it also changed its trajectory. The most strategically important shift in the years that followed was digital.

GE Transportation had spent heavily on digital solutions and analytics as part of GE’s “digital industrial” push. Wabtec brought its own foundation in electronics and train-control systems. Together, they could offer something closer to an end-to-end platform: onboard hardware, connectivity, and software that turned day-to-day operations into data.

Positive Train Control—PTC—was central to that story. PTC combines GPS, wireless communications, and onboard computing to automatically intervene before certain accidents happen, including train-to-train collisions and derailments caused by excessive speed. After years of slow adoption, federal rules ultimately required PTC across much of the U.S. rail network. That mandate created a large market for equipment, installation, and ongoing support—and Wabtec was one of the best-positioned companies to deliver it.

But safety systems were only the beginning. Wabtec pushed deeper into predictive analytics, fuel-optimization software, and remote monitoring. Modern locomotives produce massive streams of data—engine performance, fuel burn, component wear. The value isn’t the data itself; it’s what you do with it. With the right analytics, railroads can tune how trains are handled, cut fuel consumption, and spot maintenance issues before they turn into failures that strand a locomotive and disrupt the network.

The Decarbonization Imperative

As climate concerns reshaped industrial priorities, Wabtec leaned into decarbonization with a very rail-specific philosophy: don’t just talk about future concepts—build machines that can work in the real world.

The marquee effort was FLXdrive, which Wabtec described as the world’s first heavy-haul 100-percent battery-electric locomotive. This wasn’t a lab prototype. It was tested in actual operating conditions, where the constraints are unforgiving: steep grades, long trains, brutal duty cycles, and customers who care less about novelty than reliability.

In testing across more than thirteen thousand miles, FLXdrive reduced overall fuel consumption by more than eleven percent when used in consist with conventional diesel locomotives. The system could also capture energy through regenerative braking—turning downhill momentum into stored power that could be used on the next climb.

In transit, Wabtec targeted a different emissions problem—one most riders never think about. Traditional friction braking creates brake dust, a source of particulate pollution in dense subway systems. Wabtec’s Green Friction technology was shown to reduce particle emissions from friction braking by up to ninety percent, a meaningful step for air quality in cities built around metro networks.

Continued M&A Momentum

Even while digesting GE Transportation, Wabtec didn’t stop buying. In 2022, it acquired Masu, Trimble’s Beena Vision business, and Collins Aerospace ARINC—adding inspection technology, machine vision, and communications capabilities. In 2023, it acquired L&M Radiator, expanding its thermal management portfolio.

Then, in January 2025, Wabtec announced its largest post-GE deal: acquiring Evident’s Inspection Technologies business for $1.78 billion. Evident, a subsidiary of Olympus Corporation, specialized in non-destructive testing—tools that can inspect materials and components without damaging them. In rail, that’s not optional. It’s how you find cracks in rails, wheels, and structural components before they become incidents.

The Evident deal also signaled something broader about what Wabtec was becoming. Inspection technology isn’t just a one-time equipment sale. It supports recurring revenue through consumables and services, and it embeds Wabtec deeper into customers’ maintenance workflows. It also expanded Wabtec’s reach beyond rail, into wider industrial markets that rely on the same core capability: proving that critical equipment is safe, without taking it apart.

IX. Playbook: Business & Investing Lessons

The Power of Industrial Consolidation

Wabtec’s rise is a case study in what patient consolidation looks like when it’s done with a plan. Before the acquisition streak, the rail equipment world was a patchwork: dozens of specialists, each owning a narrow niche or a regional customer set. If you were a railroad or a transit agency, you didn’t so much “buy a system” as you stitched one together—brakes from here, electronics from there, service from someone else entirely.

Wabtec changed the dynamic by assembling a portfolio customers couldn’t easily recreate on their own. Breadth became a feature, not bloat. A transit agency could increasingly turn to one supplier for brakes, HVAC, door systems, and electronic controls—and then keep that same partner on the hook for global service and long-term support. That kind of simplification isn’t just convenient. It raises switching costs, deepens relationships, and gives the consolidator real leverage over time.

Managing Cyclicality Through Diversification

Rail is cyclical in a way that can punish the unprepared. When volumes roll over, new equipment orders can dry up fast—and plenty of investors have learned the hard way that “cheap” can always get cheaper in an industrial downturn.

Wabtec’s defense was diversification by design: freight balanced with transit, North America balanced with international markets, and—crucially—new equipment balanced with aftermarket.

The aftermarket piece is the stabilizer most people underestimate. Every locomotive sold, every brake system installed, every electronic platform deployed adds to an installed base that has to be maintained, repaired, and upgraded for decades. When the cycle turns down and big new orders pause, the installed base doesn’t disappear. The GE Transportation combination amplified this effect dramatically, expanding the fleet Wabtec supports and making the service stream feel closer to an annuity than a typical industrial revenue line.

M&A as Core Competency

Many companies treat acquisitions like one-off milestones. Wabtec treated them like a muscle to build.

Over decades and dozens of deals, it developed a repeatable playbook: what to buy, what to pay, how to integrate, where to cut, and what not to break. That last part matters. The goal wasn’t to strip targets for parts; it was to keep the capabilities that made them valuable while still capturing synergies with scale.

Done well, this becomes self-reinforcing. A track record of clean integrations builds trust with sellers, who want their businesses to land with an owner that will actually invest. It builds confidence with lenders and investors too, which lowers the friction cost of doing the next deal. In consolidation stories, that credibility is a competitive advantage all its own.

Technology Adoption in Traditional Industries

Railroad technology can look mature from the outside—steel wheels, steel rails, and operating practices that feel like they’ve been around forever. But Wabtec’s push into digital systems and decarbonization is a reminder that “traditional” doesn’t mean “static.”

The bigger investing lesson is simple: don’t assume old-economy industries are insulated from technological change. The winners are usually the companies that adopt new tools without abandoning the advantages they’ve already earned—relationships, distribution, certification know-how, and an installed base that can be upgraded rather than replaced. Wabtec’s strategy of pairing that installed base with digital capabilities is exactly that play.

Capital Allocation Through Cycles

Wabtec’s capital allocation priorities shifted as the company itself changed. Early on, the discipline was survival and deleveraging—paying down the debt that came with the management buyout. As the balance sheet strengthened, acquisitions became the primary use of capital, compounding the consolidation strategy. More recently, it added a more balanced approach, pairing M&A with share repurchases and dividends—returning cash while keeping flexibility for the next opportunistic swing.

The takeaway isn’t that any one approach is “best.” It’s that capital allocation has to evolve with maturity, market conditions, and the opportunity set in front of you. The mistake is rigidity—always buying, always paying down debt, or always returning capital regardless of what the moment demands. Wabtec’s willingness to change priorities as the situation changed is a big part of why the story kept working.

X. Analysis & Bear vs. Bull Case

The Bull Case

The optimistic view on Wabtec starts with a simple structural fact: in the West, there are essentially only two companies left that can build big diesel-electric freight locomotives at scale—Wabtec and Caterpillar’s Progress Rail. That kind of market shape doesn’t guarantee easy profits, but it does make the business harder to commoditize. New entrants would face enormous upfront investment, long certification cycles, and the even bigger problem of competing against incumbents with massive installed bases and decades-long customer relationships.

Then there’s the secular backdrop. Rail moves freight with materially lower carbon emissions per ton-mile than trucking, so if regulation tightens or shippers keep prioritizing carbon footprint, rail has a natural advantage—and Wabtec sits right in the middle of that potential mode shift. On top of that, Wabtec’s investments in hybrid and battery-electric locomotives could make rail even more compelling over time. In parallel, transit spending has its own long-run tailwinds: urbanization, congestion, and cities that eventually have to invest in mass transportation whether budgets feel generous or not.

The biggest “optionality” case is digital. Wabtec now has a rare combination: a huge installed base, deep onboard hardware and sensor footprint, and the analytics capabilities to turn raw locomotive and network data into action. If railroads continue adopting predictive maintenance, more automated operations, and tighter scheduling driven by software, Wabtec has a path to sell higher-margin services on top of the physical equipment it already supplies.

Finally, there’s execution credibility. Wabtec has a long track record of turning acquisitions into real operating improvement—from Faiveley to the much larger GE Transportation combination. Add in solid free cash flow generation that can fund both growth and shareholder returns, and the bull case is that you’re not just buying an industrial supplier—you’re buying a consolidator with technology upside.

The Bear Case

The bearish view starts where it usually does in rail: cyclicality. Freight volumes move with the broader economy, and when the cycle turns, locomotive orders can fall hard and stay weak for long stretches. Wabtec’s largest customers—the Class I railroads—have a long history of protecting their own cash flows first, which often means deferring equipment purchases and stretching replacement cycles. For suppliers, that can turn revenue into a roller coaster.

Even with Wabtec’s integration playbook, integration risk doesn’t disappear—it just gets managed. GE Transportation was transformational in size, and big mergers often take longer to fully settle than the original synergy slide deck implies. Aligning cultures, rationalizing systems, and simplifying overlapping organizations is multi-year work, and missteps tend to show up at the worst possible time: when demand weakens.

Competition is another overhang, especially from China. CRRC is dominant in its home market and competes aggressively in many emerging markets. Today, geopolitics and regulation limit how directly that pressure hits North America and parts of Europe. But if trade relationships normalize over time, Wabtec could face a well-resourced, low-cost competitor in categories where price matters a lot.

Then there’s disruption risk—harder to handicap, but not dismissible. Autonomous trucking could narrow rail’s labor and cost advantages on certain lanes. More speculative technologies like hyperloop remain unproven, but they sit in the background as reminders that long-haul passenger transport isn’t immune to experimentation. And shifts in energy and industry—like electric vehicle adoption—could change commodity flows that have historically mattered to rail, including coal volumes.

Lastly, leverage. Wabtec’s debt has been manageable, but it’s still a constraint. A more levered balance sheet reduces flexibility: fewer “free” swings at opportunistic deals, less room for error if end markets weaken, and more pressure to prioritize debt service when conditions get rough.

Analytical Frameworks

On a Porter’s Five Forces read, Wabtec’s picture is mixed. Supplier power is moderate, since it sources across many input markets without extreme concentration. Buyer power, however, is meaningful: Class I railroads are sophisticated, consolidated customers with real negotiating leverage. The threat of new entry is low because the capital requirements, certification hurdles, and installed-base advantages are punishing. Substitutes are a constant—trucks win on flexibility and some lanes—but rail retains structural advantages in bulk freight and long-haul intermodal. Rivalry in locomotives is constrained by the duopoly dynamic, while transit equipment tends to be more competitive and project-driven.

Through Hamilton Helmer’s Seven Powers lens, Wabtec shows several durable edges. Scale economies matter in locomotive manufacturing, where fixed costs are significant and volume smooths them out. Switching costs show up most clearly in the aftermarket: maintenance routines, parts ecosystems, and operating practices become embedded around specific platforms. Network effects aren’t a major factor here, but counter-positioning can be. Wabtec’s willingness to invest in electrification and digital systems may put slower-moving competitors in a tougher spot, especially if customers start to demand those capabilities as table stakes.

Key Performance Indicators

Two signals matter a lot when tracking Wabtec.

First: aftermarket revenue as a share of total sales. That’s a proxy for how much of the business is recurring and how deeply Wabtec is embedded in customers’ day-to-day operations. A rising mix usually means stronger durability, better margins, and more resilience when new equipment cycles soften.

Second: the orders-to-revenue ratio, or book-to-bill. It’s a simple way to watch momentum. Sustained strength above one generally points to building demand and better near-term visibility. Persistent weakness below one is the warning light that softness in orders is likely to show up in reported results down the line.

XI. Epilogue & "If We Were CEOs"

Strategic Priorities for the Next Decade

Wabtec now sits on a platform built over a century and a half of reinvention. That’s a privilege—and a trap. In rail, incumbency buys you time, but not immunity. The choices Wabtec makes over the next decade will decide whether it keeps compounding as the default “picks-and-shovels” provider to global rail, or whether it gets squeezed by new technology, new competitors, and new customer expectations.

The first mandate is decarbonization—and not as a slide-deck ambition, but as a product roadmap. FLXdrive proved that battery-electric heavy-haul isn’t science fiction. But a successful test program and a scaled commercial product are very different things. Commercialization means driving down cost, industrializing manufacturing, and—crucially—figuring out how charging infrastructure actually gets built and paid for in the real world of railroad operations.

Hydrogen fuel cells sit alongside batteries as another plausible path, especially for longer-range duties where batteries struggle with energy density. Wabtec has put chips on both squares, which is rational in a world where the “winning” propulsion technology may depend on route profiles, regulations, electricity prices, and what customers can operationalize. The hard part is deciding how long to preserve that optionality before committing serious capital and engineering focus. Either way, these are long bets that require patience measured in years and, potentially, decades.

The second frontier is autonomy. Fully autonomous trains already exist in limited settings, like remote mining operations. The leap is taking that concept into the messy, high-traffic, mixed-asset reality of mainline freight. Wabtec has a head start with Positive Train Control as a safety foundation, but true autonomy demands more than compliance-grade safeguards. It requires next-level sensing, decision-making software, and fail-safe engineering that railroads and regulators will trust. Whoever solves that problem at scale won’t just sell more equipment—they’ll reshape the economics of the industry.

International Expansion

Growth is also geographic. Rail investment is accelerating in pockets around the world: India modernizing its network, Southeast Asia building new connections, and Europe facing the inevitable replacement cycle of aging fleets and infrastructure. Wabtec already has a global footprint to compete for that demand, but it won’t be a victory lap. Local incumbents—often backed by governments—will fight hard for strategic projects.

And then there’s China, the ever-present shadow over global rail manufacturing. CRRC’s scale and state support make it a formidable competitor in any market it prioritizes. Political barriers may limit how directly that competition reaches certain Western markets today, but barriers can shift. Wabtec’s best defense is the oldest one in industrial history: staying far enough ahead on technology, reliability, and lifecycle support that customers are willing to pay for the difference.

Portfolio Decisions

Finally, there’s a CEO question that never really goes away in diversified industrials: what belongs together?

Transit and freight live on different cycles and sell to different customers. Components and full systems require different muscles. The case for keeping it integrated is the one management has leaned on: shared technology platforms, manufacturing capabilities that can be leveraged across segments, and diversification that smooths the peaks and valleys of a cyclical industry.

But markets have a habit of revisiting that argument, especially when performance stumbles or when a part of the portfolio starts to look undervalued inside the whole. Breakups and spin-offs have become a familiar activist playbook in industrial America. Wabtec doesn’t have to agree with that logic to respect it—and to operate with the awareness that today’s structure is a choice, not a law of nature.

Final Reflections

George Westinghouse built his company around a single mission: make trains stop safely. A century and a half later, the company that still carries the echo of his name is solving the same category of problem—just with different tools. Software, sensors, analytics, advanced materials, and new propulsion technologies are all in service of the same fundamentals: moving people and goods efficiently, reliably, and safely.

Wabtec’s story is, in its own way, a condensed history of American industry: invention followed by scale, disruption followed by adaptation, and consolidation executed by leaders who treated capital allocation as a craft. It survived the decline of rail’s golden age, reemerged through a management buyout, and then built a modern platform through disciplined M&A—culminating in the acquisition of GE’s locomotive franchise. Along the way, the installed base and customer relationships created by Westinghouse-era braking systems evolved into something even more powerful: decades-long partnerships where Wabtec is embedded in how railroads operate.

For investors, Wabtec is a bet that rail remains essential—and may become even more so in a carbon-constrained world. For students of strategy, it’s a living case study in how to build durable advantage in a cyclical, high-barrier industry: diversify intelligently, obsess over the aftermarket, and acquire with discipline. And for anyone wondering whether “old economy” companies can still win in the twenty-first century, Wabtec’s answer is simple: yes—but only if they keep earning it.

XII. Recent Developments

Over the past several quarters, Wabtec’s story has been less about dramatic pivots and more about execution—doing the blocking and tackling that turns a strategy into results. The clearest signal was the January 2025 announcement that it would acquire Evident’s Inspection Technologies business for $1.78 billion. It was the company’s largest deal since GE Transportation, and it pushed Wabtec further into inspection and non-destructive testing—technology that fits naturally with rail’s safety-and-reliability DNA and also opens doors into adjacent industrial markets.

Management also highlighted continued progress capturing synergies from earlier acquisitions, while still funding organic initiatives—especially in digital solutions and sustainability-focused technology. On the demand side, orders across both Freight and Transit remained constructive, helped along by infrastructure investment programs in North America and Europe.

In Freight, the locomotive backlog moved around quarter to quarter, but it continued to provide the kind of multi-year visibility that’s rare in cyclical industrials. In Transit, orders tracked the long, steady forces that tend to drive that business: urbanization and the ongoing buildout of metro and passenger rail systems, particularly across Asia and Europe.

XIII. Links & Resources

Company Filings and Investor Materials

- Wabtec annual reports and Form 10-K filings on the Securities and Exchange Commission’s website

- Quarterly earnings presentations and earnings call transcripts

- Investor Day presentations outlining strategy, priorities, and financial targets

- Proxy statements covering executive compensation, incentives, and governance

Industry Analysis

- Association of American Railroads statistical publications and industry overviews

- Surface Transportation Board filings and regulatory reports

- Railway Age and Progressive Railroading archives for ongoing industry coverage

- Federal Railroad Administration safety data, rules, and enforcement updates

Historical References

- Steven W. Usselman, Regulating Railroad Innovation: Business, Technology, and Politics in America, 1840-1920

- Maury Klein, Union Pacific: The Rebirth, 1894-1969

- Richard Saunders Jr., Main Lines: Rebirth of the North American Railroads, 1970-2002

- Quentin R. Skrabec Jr., George Westinghouse: Gentle Genius

Technical Deep Dives

- American Railway Engineering and Maintenance-of-Way Association (AREMA) technical bulletins

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) papers on Positive Train Control

- Environmental Protection Agency locomotive emissions regulations and supporting analysis

- U.S. Department of Transportation studies on rail efficiency and freight transportation economics

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Chat with this content: Summary, Analysis, News...

Amazon Music

Amazon Music